Sayer Ji

Sep 10, 2025

Read, comment, and share the X post dedicated to the article here: https://x.com/sayerjigmi/status/1966177345255125131

Inorganic calcium supplements derived from limestone, egg shell, and oyster shell -- long touted as an insurance policy against osteoporosis -- are now implicated in serious health harms. A growing body of research (including meta-analyses and clinical trials) has linked supplemental calcium to increased rates of heart attacks, arterial calcification, kidney stones, and even higher risk of certain cancers, despite modest gains in bone density. This exposé examines how a well-intentioned public health trend went awry, driven in part by profit motives and flawed definitions that pathologized normal aging in women.

Key takeaways include:

Cardiovascular Dangers: Multiple large studies (including in the British Medical Journal) found that taking elemental calcium supplements (≥500 mg/day) is associated with a 20–30% increased risk of heart attacks and other cardiovascular events, even when vitamin D is co-administered. One 11-year study of 24,000 adults found supplement users were 86% more likely to have a myocardial infarction than non-users -- prompting editors to warn that bolus calcium doses "are not natural" and may calcify arteries instead of protecting the heart.¹²

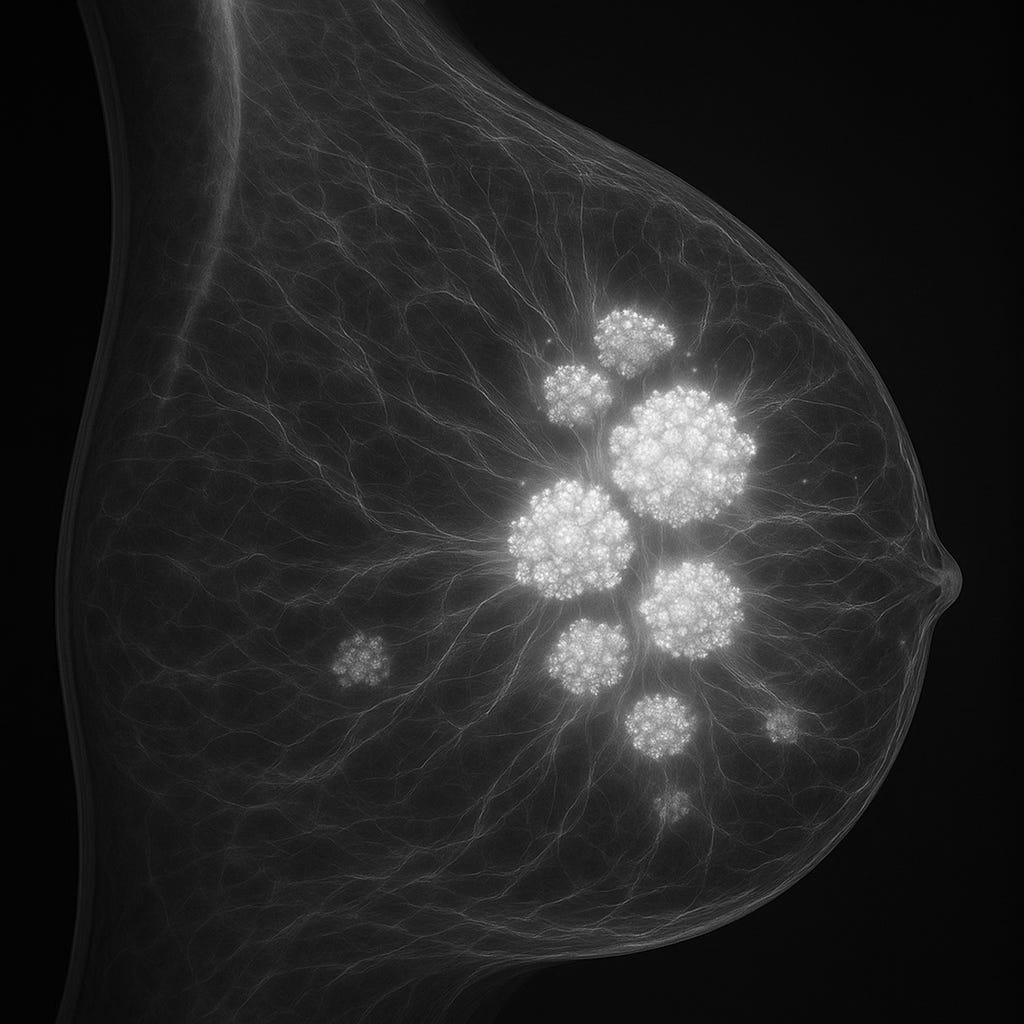

Breast Cancer Links: Higher bone density (often the goal of calcium supplementation) correlates with increased breast cancer risk. Epidemiological research has shown postmenopausal women with low bone density actually have significantly lower rates of breast cancer and recurrence compared to those with "normal" or high density.³⁴ Conversely, women in the highest bone density ranges (often achieved via lifelong calcium loading or bone drugs) have been found to have a 200–300% higher incidence of malignant breast cancer.⁵ Calcium deposits in breast tissue (seen as microcalcifications on mammograms) may not be harmless: emerging evidence suggests hydroxyapatite crystals can act as signaling molecules that spur local cell growth and even trigger malignant changes, meaning some calcifications could cause tumors rather than merely accompany them.⁶

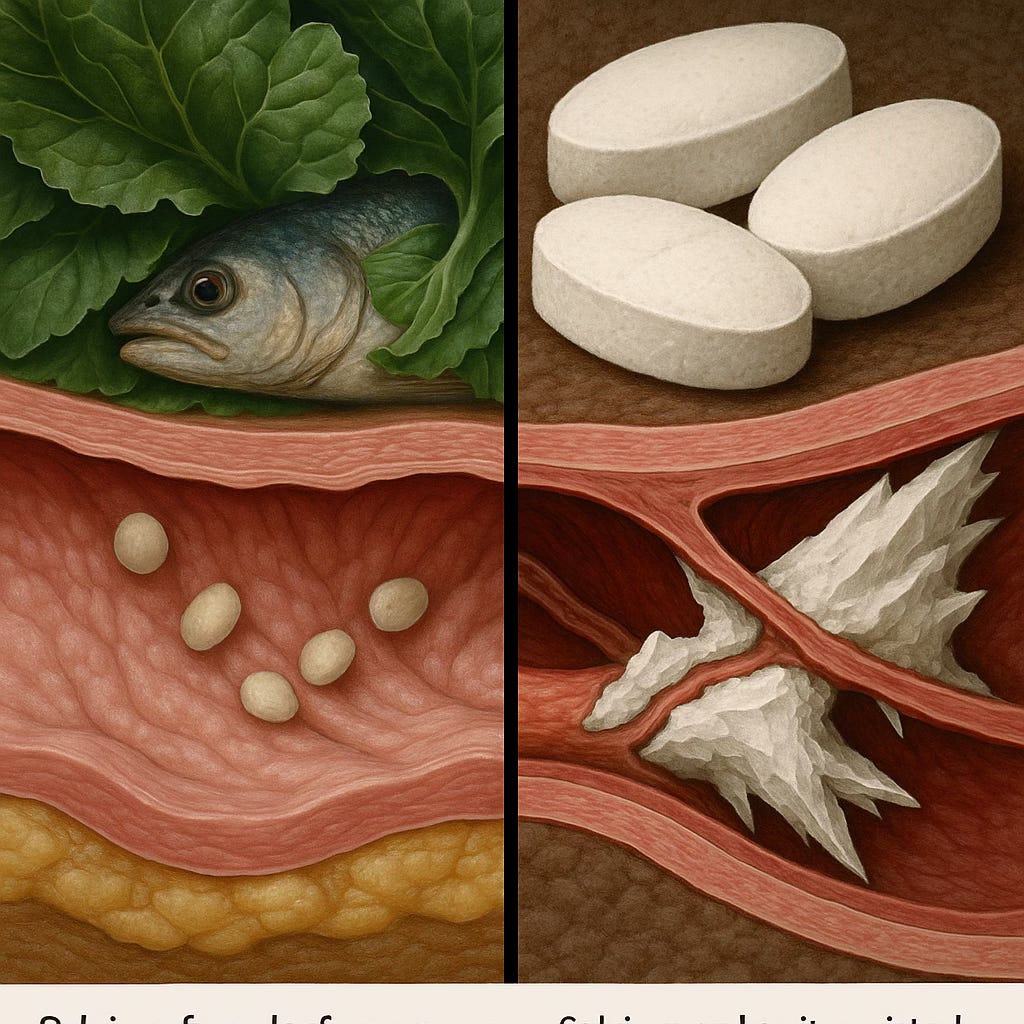

Soft Tissue Calcification & Kidney Stones: Calcium that is not incorporated into bone can end up in arteries, kidneys, and other soft tissues, with destructive results. Excess calcium from elemental calcium supplements contributes to artery stiffening (arteriosclerosis) by contributing to the formation of a brittle mineral cap on arterial plaques, increasing heart attack risk.⁷ The Multi‐Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) showed that high dietary calcium reduced 10-year risk of coronary artery calcification, yet those taking supplements had a 22% higher risk of developing coronary calcifications -- essentially counteracting the cardiovascular benefits of calcium.⁸⁹ Calcium supplements also raise urinary calcium levels and have been linked to kidney stones: unlike calcium from food (which actually protects against stones), calcium in pills can overload the body's handling capacity, leading to stone formation in susceptible individuals.¹⁰ Doctors report a 17–20% increase in kidney stone incidence among women on calcium supplements, and advise obtaining calcium through diet whenever possible.

Bone Density vs Bone Quality: Paradoxically, loading up on calcium pills can yield denser but more fragilebones. Research confirms that simply increasing bone mineral density (BMD) does not necessarily translate to stronger bones or fewer fractures. For example, earlier osteoporosis treatments like fluoride produced higher BMD on scans but caused brittle bones and more fractures, as the bone's micro-architecture and collagen quality were compromised.¹¹ Likewise, extensive reviews have found no clear reduction in fracture risk from calcium supplementation, despite small BMD increases; any skeletal benefit is at best modest and not guaranteed.¹² In fact, one analysis concluded "the non-skeletal risks of calcium supplements appear to outweigh any skeletal benefits" -- a stark warning that adding calcium for its own sake may do more harm than good.¹³

From Essential Nutrient to Potential Toxin

Calcium is essential for human health, but dosage and delivery matter enormously. In food, calcium is accompanied by cofactors (other minerals, protein, vitamins like K2 and D) that help guide it into bones and keep it out of arteries. Supplements, by contrast, often provide "elemental" calcium (carbonate, citrate, or phosphate derived from rocks, bones, or shells) in isolation.¹⁴ Taking a calcium pill on an empty stomach delivers a large, unbuffered calcium bolus into the bloodstream. This results in a sharp spike in serum calcium that overwhelms the body's regulatory mechanisms. One clinical nutrition review explains that a single large calcium dose from a supplement causes blood calcium to surge, forcing the body to dump the excess into tissues or urine. In contrast, calcium from food is absorbed gradually (especially when consumed with protein and fiber), so calcium trickles into the blood at a rate the body can manage and incorporate into bones.¹⁵ As the review put it, "the calcium is either deposited in arteries or excreted via kidneys" when taken in pill form, whereas dietary calcium "reach[es] bones and other cells where it is required".¹⁶

Scientists now suspect that these unnatural calcium spikes are the key to why supplements cause harm. The body perceives persistently high calcium levels as a red flag -- triggering hormonal responses to tone down calcium absorption and ramp up calcification processes. Calcium-sensing receptors in blood vessels may induce arterial calcification when activated by surges of calcium, and the excess calcium can directly crystallize pathologically as hydroxyapatite in soft tissues.¹⁷¹⁸ Histological studies show that sites of ectopic (out-of-place) calcification -- whether in arteries, heart valves, or breast tissue -- are often infiltrated by bone-associated proteins. For instance, osteopontin, a bone matrix protein, is abundantly upregulated at calcified spots in blood vessels (essentially the body attempting to regulate or wall off the crystal deposits).¹⁹ Similarly, osteonectin (another bone protein) has been identified as an active promoter of calcification in vascular tissue.²⁰ These findings reveal that calcium deposits can hijack cellular signaling, transforming soft tissue cells into bone-like cells. In effect, high supplemental calcium can make your arteries act like bone -- hardening them with mineral. This pathophysiology underlies the observed spikes in heart attack and stroke risk among calcium supplement users.

Notably, a 2012 German study in the journal Heart brought this issue to national headlines. Tracking ~24,000 middle-aged adults for 11 years, researchers found those who used calcium supplements regularly had an 86% higher heart attack risk compared to non-users.² Participants who got their calcium exclusively from supplements (with little dietary calcium) fared even worse -- they had a 2.7-fold higher risk of myocardial infarction.²¹ The study concluded that while high dietary calcium intake appeared cardio-protective, "calcium supplements, which might raise MI risk, should be taken with caution."²² An accompanying editorial in Heart bluntly stated that dosing calcium once or twice a day in pill form "is not natural, in that it does not reproduce the same metabolic effects as calcium in food."²³ In other words, the convenient supplement shortcut bypasses the body's slow-and-steady calcium absorption controls -- with grave consequences.

Hardening Arteries and Heart Attacks

Perhaps the most alarming harm linked to calcium supplements is their impact on the cardiovascular system. Arterial plaques -- the fatty lesions in our arteries that can lead to heart attacks -- undergo a well-known "calcification" process as they advance. Calcium deposits stiffen the plaques (much like lime scale hardens pipes), which can lead to plaque rupture. It's now understood that excess circulating calcium accelerates this process. High-dose calcium supplementation has been shown to increase coronary artery calcification scores and the instability of atherosclerotic plaques.⁷

Large-scale evidence backs this up. A landmark 2010 meta-analysis pooled data from 15 randomized trials (over 8,000 patients) and found a 27% increase in heart attack (myocardial infarction) incidence in groups assigned to calcium supplements (≥500 mg/day) versus placebo.²⁴ Importantly, these were trials primarily in older adults taking calcium for bone health -- yet the calcium group unexpectedly had more heart events. Critics wondered if co-administering vitamin D (often given with calcium) would mitigate the risk, but a follow-up meta-analysis in 2011 showed virtually the same increase in heart attacks (~24%) in patients taking calcium with vitamin D.²⁵ In other words, adding vitamin D -- while beneficial for other reasons -- did not counteract calcium's artery-hardening effects. These twin analyses, published in the British Medical Journal, sent shockwaves through the medical community, calling into question the safety of a supplement that millions considered benign.¹²

Subsequent studies reinforced the cardiovascular warning. The MESA study (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) used CT scans to observe how calcium intake affected the development of coronary calcifications over 10 years. The results were telling: Participants with the highest dietary calcium intake actually had lower risk of developing new calcifications, presumably because diet-derived calcium comes packaged with other nutrients (and perhaps because those individuals had overall healthier diets). However, those who took calcium supplements had a significantly higher incidence of calcified arteries. After controlling for diet, supplement users showed a 22% uptick in risk of any new coronary artery calcification forming over the decade.⁸⁹ This dichotomy -- food calcium helping, pill calcium harming -- underscores that how we get calcium matters profoundly for heart health.

Other research has tied calcium supplements to higher blood pressure and arrhythmias, possibly due to calcium's role in vascular tone and cardiac electrical activity.²⁶ It's no coincidence that calcium-channel blocker drugs (which lower calcium's entry into heart and artery muscle cells) are widely used to treat hypertension -- too much free calcium stiffens blood vessels and overexcites the heart. In some individuals, calcium supplements precipitate dangerous arterial spasms or erratic heart rhythms (reported as "heart cramp" or atrial fibrillation triggers).

It is now recognized that coronary artery calcification (CAC) is a strong predictor of future cardiac events. By unnecessarily boosting CAC, calcium supplements may be converting an essential mineral into a cardiovascular toxin. As two Auckland University professors wrote, calcium supplementation's safety "is now coming under increasing scrutiny," given that these pills flood the bloodstream with calcium in a way that nature never intended.²⁷ Their advice: reserve calcium supplements only for medical necessity -- if at all -- and rely on food sources whenever possible.²⁸²⁹ For most people, a balanced diet (with adequate vitamin D and K2) can maintain bone health without risking one's heart. Unfortunately, for years many doctors reflexively told older patients (especially women) to take 1,000–1,500 mg of calcium daily, not realizing they may have been trading stronger bones for a weaker heart.

Calcifications, Cancer, and Misdiagnosed "Disease"

One of the more startling associations with calcium supplementation is breast cancer, particularly in postmenopausal women. On the surface, bone density and breast cancer would seem unrelated -- yet multiple studies over the past two decades have drawn a connection between higher BMD and higher breast cancer incidence. The link likely involves hormonal factors (e.g. estrogen both increases bone density and can fuel certain breast cancers) as well as shared pathways of calcium metabolism and cell proliferation.

A 2013 analysis in The Breast Journal confirmed a trend that previous investigations had hinted at: women with low bone density had lower rates of breast cancer and better prognosis if they did develop breast cancer.³⁴ In that study of 309 breast cancer patients, those with below-average BMD had a 5-year disease-free survival of 96% versus only 84% in women with normal/high BMD -- a significant difference.⁴ This finding supports the controversial hypothesis that "the lower your bone density, the lower your breast cancer risk." It starkly contradicts the popular notion that morebone density is always better.

How might bone density tie into cancer? One theory centers on the role of calcium deposits in breast tissue. Mammograms often detect microcalcifications -- tiny calcium flecks -- in the breast. While many microcalcifications are benign (including conditions like ductal carcinoma in situ, which were wrongly treated like early malignancies for decades), there are nonetheless breast calcification associated patterns linked to fast-growing, highly malignant forms. What's intriguing is how these calcifications form. They are essentially hydroxyapatite crystals, the same mineral in bone (relative to more benign formations in the breast known as calcium oxalate). Researchers have discovered that hydroxyapatite crystals can send powerful signals to nearby cells: they act as a mitogen, meaning they can stimulate cells to divide.⁶ In a breast duct, a cluster of calcium crystals might provoke the surrounding epithelial cells to proliferate uncontrollably -- potentially initiating cancer. In fact, some scientists have postulated that calcifications may precede and promote tumor growth, not merely result from it.³⁰ This flips the script on the old assumption that calcium deposits in tumors are just a byproduct; instead, they could be active instigators of malignancy.

Moreover, if a woman has excess calcium floating in her system (due to supplements), she may be more prone to depositing calcium in breast tissue -- essentially "seeding" the area with potential hotspots for cancerous change, or providing the ideal tumor microenvironment whereby a phenotypic transformation occurs: the healthy breast cell transforms into a malignant, bone-seeking (metastatic) breast cell. Autopsy studies note that women who took high-dose calcium often exhibit calcium in tissues all over the body -- even in the brain (so-called "brain gravel" found in the pineal gland and other regions).³¹ The breasts, being glandular tissue with good blood supply, are certainly a potential landing zone for extra calcium. Indeed, clinicians have observed benign breast arterial calcifications (visible on mammograms as linear streaks) in women on long-term calcium therapy or certain medications (like thiazide diuretics, which cause calcium retention).³²³³ These calcifications can complicate mammography by obscuring images or prompting unnecessary biopsies. In essence, the same X-rays used to measure bone density (DEXA scans) are also used to detect breast calcifications -- a poetic illustration of how calcium can be a double-edged sword in women's health.³⁴

From a public health perspective, the calcium supplement boom and the mammography surge have created an ironic feedback loop. Women were told to take calcium to prevent osteoporosis; many postmenopausal women obliged. Years later, some of these same women receive mammograms that find calcifications -- which may lead to anxiety, invasive investigations, or even overdiagnosis of indolent lesions. We are essentially witnessing how the medicalization of normal aging can spiral into unintended harms.

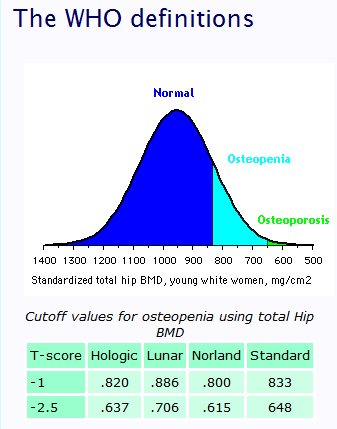

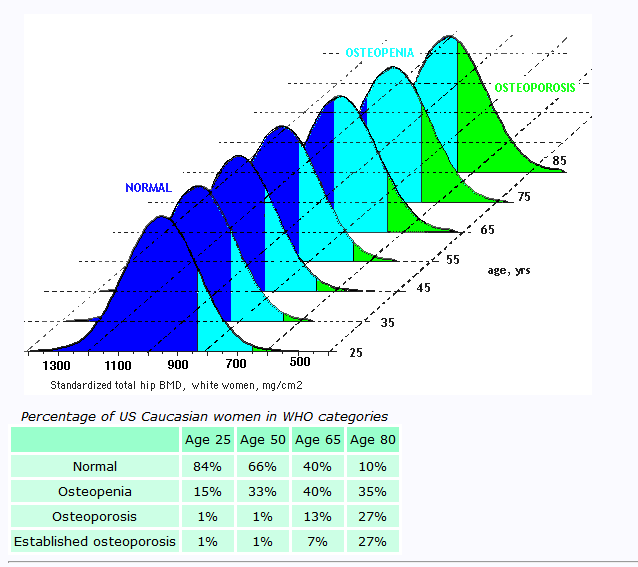

No case better epitomizes this than the story of osteoporosis screening and the T-score. In 1994, the World Health Organization (WHO), influenced by new bone density technology, established a definition of osteoporosis based on a statistical comparison to young adults. Specifically, they defined osteoporosis as having a BMD 2.5 standard deviations below that of an average 25-30 year-old woman (this measurement is known as the T-score). This seemingly arbitrary cutoff reclassified a huge swath of older women as diseased -- essentially labeling the natural, gradual bone loss of aging as an illness. By the stroke of a pen, millions of healthy women in their 50s, 60s, and beyond were told they had "osteopenia" or "osteoporosis," even if they felt perfectly well and had no fracture history. This redefinition has been described as a classic case of disease mongering: turning normal aging into a pathology.

The immediate result was a massive expansion in the market for bone density scans, calcium supplements, and osteoporosis drugs. Pharmaceutical companies like Merck, which launched the bisphosphonate drug Fosamax around that time, heavily promoted bone density screening. The National Osteoporosis Foundation (funded by supplement and pharma interests) echoed the call. Unsurprisingly, sales of calcium supplements and prescriptions for bone medications skyrocketed. It was a highly successful campaign from a business standpoint -- but many researchers and clinicians now question if it was ethically or scientifically justified.³⁵ Common sense tells us that comparing an 70-year-old's bones to a 25-year-old's is flawed: of course the older bones are less dense, but are they abnormal? By confusing statistical norms with health, the WHO criteria may have overdiagnosed millions and set them on a path of needless treatment.

Importantly, subsequent evidence has shown that chasing higher bone density at all costs can backfire. One unintended consequence of the "bone density at any cost" mindset is the aggressive use of calcium supplements -- and as we've detailed, that has likely contributed to more cases of heart disease and perhaps cancer. Another consequence has been the overuse of potent bone drugs (like bisphosphonates), which indeed increase BMD but at the expense of bone quality, leading to rare but serious fractures (such as atypical femur fractures and jaw necrosis). The overdiagnosis of osteoporosis also diverted attention from more holistic approaches to bone health (nutrition beyond calcium, exercise, vitamin D/K2, hormonal balance, etc.). In short, by redefining aging as disease, we prescribed quick fixes (like calcium pills) that introduced new problems.

Watch Dr. Michael Greger’s video to learn more about the harms of osteoporosis drugs.

Even mainstream experts have begun to acknowledge this misstep. The authors of the 2015 BMJ review on calcium and fractures concluded that there is no solid evidence that increasing calcium intake (by diet or supplements) after age 50 significantly prevents fractures.¹² Yet, as they noted, millions of adults were already taking supplements or being advised to do so -- essentially an uncontrolled public health experiment. Now, accumulating data on cardiovascular and cancer outcomes are forcing a reckoning. As one professor quipped, "we have been treating a bone density number rather than the patient." Bone strength is about quality, not just quantity of mineral -- a dense but brittle bone is still prone to break. Likewise, "normal" age-related changes (like slight bone thinning or some breast calcifications) may not always warrant aggressive intervention. The calcium supplement saga exemplifies how simplifying health to "more is better" can be perilous.

In fact, bone has far greater compressive strength (resisting weight-bearing loads) than tensile strength (resisting pulling forces), reminding us that density alone cannot define resilience. A bone may look “normal” on a scan yet still fracture if its microarchitecture is compromised — underscoring that true bone strength is a marriage of density, composition, and quality.

Consider the difference between a material like concrete (high density; high compressive strength; low tensile strength) and bamboo, which is much more like human bone (lower density; lower compressive strength; much higher tensile strength).

The Bone Health Profit Motive and Gender Bias

It is instructive to ask: who benefited from the calcium supplement boom? Certainly, supplement manufacturers saw profits soar. So did pharmaceutical firms selling osteoporosis medications, which were often recommended alongside calcium. Diagnostic imaging companies and clinics offering bone density (DEXA) scans also gained a steady stream of new customers after the WHO's 1994 reclassification. There were clear financial incentives to medicalize bone loss and to push calcium as an easy preventative measure. Organizations like the National Osteoporosis Foundation -- whose corporate sponsors include major calcium supplement brands -- heavily promoted the "calcium paradigm" for bone health.³⁶³⁷

Shameless advertising and public health messaging in the 1990s–2000s consistently portrayed the new WHO definition of osteoporosis as a serious health threat ‘without symptoms,’ pushing extremely dangerous drugs like Fosomax, as well as calcium supplements as essential for every midlife woman, creating a virtual obligation to consume chalky tablets daily. Slogans like "Got Milk?" (backed by the dairy industry) further reinforced the notion that more calcium = strong bones. Little to no attention was paid to how calcium is utilized in the body, or the necessity of co-factors like magnesium, vitamin K2, and vitamin D -- knowledge long understood by nutritional biochemists but often ignored in clinical practice.

Some observers have also noted a gendered if not outright misogynistic aspect to this saga. Osteoporosis primarily affects women (especially postmenopausal women), and thus women have been the prime targets of bone density screening and supplement marketing. By redefining the T-score to lump the majority of older women into a "low bone density" category, the medical establishment subjected a generation of women to anxiety about their bone health -- and to lifelong treatments with uncertain benefit. This occurred despite the fact that men too suffer fractures and osteoporosis (albeit at older ages on average), yet men were not screened or medicated at nearly the same rates.

Pictured above is a Caltrate calcium supplement ad, with the tagline “One in every three women will develop osteoporosis.” - a true statement, when applying the inappropriate WHO, 30-year old woman at peak bone mass, T-score based definitions of bone disease.

The emphasis on women's bones can be seen as a double-edged sword: while it's important to address postmenopausal fracture risk, the approach taken may have patronized and over-medicalized women's normal physiology (menopause and aging) for profit. In the process, women were often given simplistic advice ("take your calcium pills") that ignored underlying issues like hormone changes or nutrient synergy. Indeed, as Dr. Suzanne Humphries provocatively argued, osteoporosis is not a calcium deficiency at all, but rather a collagen/vitamin C deficiency -- "scurvy of the bone."³⁸ Her viewpoint highlights that bone fragility stems from more than just mineral loss; the protein matrix (which depends on vitamin C, among other factors) is crucial for bone toughness. By fixating on calcium, mainstream medicine may have missed the forest for the trees.

The "osteoporosis industrial complex" -- comprising supplement companies, pharma, and even advocacy groups -- undoubtedly influenced medical guidelines. Financial ties were later exposed, showing conflicts of interest in panels that set calcium and vitamin D intake recommendations. The result was an oversimplified narrative: women were told that consuming lots of calcium (and recently, vitamin D) would save them from fractures, and that any deviation from youthful bone density was a disease in need of treatment. Lost in this narrative were the potential risks of those interventions and the complexities of bone biology. Only in the last decade has the paradigm begun shifting, as independent analyses reveal calcium supplements' dark side and as doctors witness unexpected complications in patients on long-term calcium and bone drugs (such as calcium-rich plaques, kidney stones, or atypical fractures).

Rethinking Calcium and Bone Health + My Personal Recommendations

In light of the evidence, a critical reappraisal of routine calcium supplementation is urgently needed. The harms—heart attacks, strokes, arterial calcification, kidney stones, breast cancer, dementia—are too serious to ignore. Meanwhile, the intended benefit (fracture prevention) has not clearly materialized in randomized trials, except in narrow cases like institutionalized elders with severe vitamin D deficiency. For most people, simply taking a calcium pill does not guarantee stronger bones—it may instead be laying down calcium in places we don’t want it.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario