It

was the biggest drug seizure on an airplane in Mexican history. It led

directly to the forced sale of Wachovia, then America's 4th largest

bank. And it threatened to become America’s most notorious drug scandal

since Iran Contra.

Yet

when a leader of the drug smuggling organization responsible for the

flight of the DC-9 airliner dubbed “Cocaine One” that was busted in the

Yucatan carrying 5.5 tons of cocaine quietly pled guilty to unrelated

drug charges two years ago in a Federal Court in Miami, his role in the

massive drug move was kept secret from officials preparing his

Pre-Sentence Report (PSI), from journalists, and even from the Federal

judge in the case.

Since the omission was recently discovered, tongues on two continents have been wagging.

A catch & release arrest policy for drug traffickers

Since

it began, in April 2006, the scandal of the “Cocaine One” DC-9 busted

carrying 5.5 tons of cocaine in the Yucatan has seen its share of

bizarre developments.

The

drug pilot flying the DC-9, Carmelo Vasquez Guerra, for example, had

been arrested and released in three separate countries—Mexico, Guinea

Bissau, and Mali—before Venezuela finally stepped in and put him (at

least temporarily) behind bars.

But with a shocking new revelation, the scandal has taken a sudden turn for the surreal.

The man in charge of bringing the 5.5 tons of cocaine north in one fell swoop was identified by investigators as “Raul Jimenez Alfaro.

Turns out, that's not his real name.

When cartel kingpin Jimenez Alfaro was convicted on unrelated drug charges two years ago in a Federal Court in Miami, according to investigative reporter Joseph Poliszuk at El Universal in Caracas, his

role in running the massive 5.5 ton drug move, which eventually

brought down America's 4th largest bank, went undisclosed, and remained secret.

Thus

ended the indifferently-motivated but highly secretive US

investigation, which concluded that the finger of blame in the scandal

should point to Venezuela, to Colombia, and to Mexico.

The finger of blame should point to, in other words, anywhere but here.

“Operation Seven Trumpets.”

The trial two years ago was of a man who had used the alias Raul Jimenez Alfaro.

The trial two years ago was of a man who had used the alias Raul Jimenez Alfaro.

His name, as listed on the indictment, was Luis Fernando Bertulucci Castillo.

Turns out, that’s not his real name either.

He was busted along with 34 others in something the DEA, FBI & ICE were calling “Operation Seven Trumpets," presumably a reference to the seven trumpets which sound as the cue for the Apocalypse, according to the Book of Revelations.

The

man with a deliberately foggy past is a 52-year old Mexican commercial

pilot of Italian ancestry, whose Sinaloa cartel nicknames are “El

Capitan" and "The King."

The

man with a deliberately foggy past is a 52-year old Mexican commercial

pilot of Italian ancestry, whose Sinaloa cartel nicknames are “El

Capitan" and "The King."

His real name (he says) is Fernando Blengio-Cesena.

He

has also gone by Fernando Blengio Cesena; Luis Fernando Bertulucci;

Fernando Bertulucci Castillo; Fernando Blengio Cesena Bertulucci; and

Luis Fernando Castillo.

A Miami Moment

It was one of those “only in Miami moments” encountered every so often in judicial proceedings involving drug trafficking in South Florida.

It was one of those “only in Miami moments” encountered every so often in judicial proceedings involving drug trafficking in South Florida.

In

a hearing before District Court Judge Patricia Seitz, Raul, or rather

Fernando, modestly admitted to having three aliases. Courthouse

observers suggest that if he’s admitting to three, he probably

forgetting another half-dozen.

While Assistant US Attorney Andrea Hoffman looked on, Fernando Blengio admitted using the alias "Raul Jimenez Alfaro" before a Federal Judge.

The admission elicited no comment from either. From court transcripts:

JUDGE: How many aliases do you have?

A.

The truth, besides the other one, Luis Antonio Ortega Sandoval. With

the other aliases that I had I was also flying, and I had the license,

and I was also doing commercial jobs, executive flights, charters and

aerial ambulance flights.

JUDGE: Under the Bertulucci name?

FERNANDO: Well, unfortunately also under the name of Raul Jimenez Alfaro.

Why

"unfortunately?' Fernando is not asked. But observant reporter

Poliszyk noted that this was an admission that he was the man who had

helmed the drug operation moving 5.5 tons of cocaine from Colombia to

the US.

Why

"unfortunately?' Fernando is not asked. But observant reporter

Poliszyk noted that this was an admission that he was the man who had

helmed the drug operation moving 5.5 tons of cocaine from Colombia to

the US.

As

Raul Jimenez Alfaro, he had coordinated bribes to Mexican officials at

three regional airports which were receiving deliveries of part of the

5.5 ton cocaine load went unmentioned.

He

also owned the Falcon business jet which had mysteriously flown to the

Yucatan to meet the DC-9 at the airport in Ciudad del Carmen in the

Yucatan. The Falcon was under contract to the Mexican Water Commission,

which was run by the former head of Coca Cola de Mexico, a long-time

crony of Mexican President Vicente Fox.

None of this came to light at his sentencing.

Lying is okay if it's a matter of national security.

Fernando

was sentenced to 13 years in prison. His light sentence was a reward

for serving as an informant for the Assistant US Attorney in charge of

his case, Andrea Hoffman, who prosecutes many of Miami’s big-time drug

cases, including all those from Colombia.

Fernando

was sentenced to 13 years in prison. His light sentence was a reward

for serving as an informant for the Assistant US Attorney in charge of

his case, Andrea Hoffman, who prosecutes many of Miami’s big-time drug

cases, including all those from Colombia.

Yet

Hoffman must have known of the role he had played in the 5.5 ton DC-9

saga, because she had also been involved in the prosecution of Mexican

currency exchange Casa de Cambio, which laundered the money used to

purchase the DC-9, investigators determined, through Wachovia Bank.

Why

would Hoffman keep information on Fernando's past exploits secret? Was

her job, in part, keeping the U.S.'s dirty drug dealings secret—not from

drug cartels, who presumably know all about them—but from American citizens?

Assistant US Attorney Andrea Hoffman, in fact, has secrets of her own which may offer an answer. For example, this is not the first time she has faced questioning while serving as lead prosecutor over her conduct in a criminal case.

Hoffman

has been accused or faced sanctions for withholding crucial information

from the defense in felony drug trafficking cases on at least several other occasions.

"Everybody bugs defense attorneys. Ask the NSA"

Because

of recent miscues, two of Fernando’s "associates" from Colombia—who

might have been expected to spend a decade or more in prison—will soon

be heading home.

John Winer and Jose Buitrago were accused of conspiring with drug traffickers from Colombia to secure airplanes for the purpose of transporting drugs, basically the same thing Fernando was charged with.

Lawyers

for the two, from the office of the Federal Public Defender of the

Southern District of Florida, asked prosecutors to turn over records of

payments from the DEA to officers who investigated their client.

The men's attorney's suspected that Colombian police officials had been paid to implicate them.

The

prosecution was ethically and legally bound to turn the information

over to the defense. But Andrea Hoffman insisted that no payments were

made to Colombian law enforcement.

That

was contradicted by the first witness, an officer from the Colombian

police, as well as a DEA agent, who testified that Hoffman knew about

the payments. Over the course of three years, 11 members of Colombian

law enforcement received payments of $200 per month from the U.S.

A pattern of deception

The

judge said she was "personally frustrated and disappointed" at Hoffman

and did not believe the prosecutor's claims that she had not been aware

of the payments at the start of the trial.

"I

think the United States was aware that Colombian police officers, in

the course and scope of their duties, received payment," she said at a

hearing last month.

"I think they were aware of it and for whatever reason, did not disclose that to defense counsel."

Hoffman was suspected of other examples of deception, even more egregious.

"2 FEDERAL PROSECUTORS CONDEMNED" read the headline in the South Florida Sun – Sentinel.

In

another case, after two prosecution witnesses secretly recorded their

phone conversations with the defense team, with approval from prosecutor

Hoffman, U.S. District Judge Alan Gold ordered the U.S. government to

pay sanctions topping $600,000 to the defense.

Calling the actions of Andrea Hoffman "profoundly disturbing,"

Gold grilled the government team at a two-day hearing to determine

whether the U.S. government should pay part of the defense's legal

fees.

Then, in a harshly-worded order, he wrote that the "win-at-any-cost behavior"

of federal prosecutors Andrea Hoffman and Sean Cronin raised “troubling

issues about the integrity of those who wield enormous power over the

people they prosecute."

"Forget integrity. Look at the history of lies."

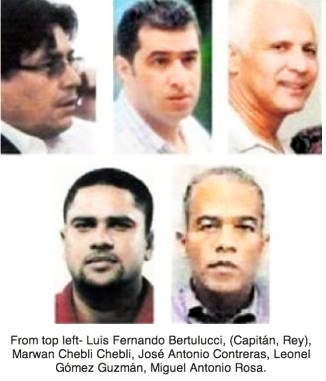

Fernando Blengio-Cesena was a trusted lieutenant of cartel boss Shorty Guzman. The criminal network which Federal authorities in Mexico and the US claim to have dismantled is part of the Sinaloa Cartel.

Fernando Blengio-Cesena was a trusted lieutenant of cartel boss Shorty Guzman. The criminal network which Federal authorities in Mexico and the US claim to have dismantled is part of the Sinaloa Cartel.

Today

the Sinaloa Cartel serves as the DEA’s all purpose drug cartel

bogeyman. There are reasons to be skeptical of the truth of the claim,

or whether, if true, it is telling anything like the whole story.

Consider

the criminal network’s leaders: Fernando Blengio-Casena, of obvious

Italian parentage, was born and raised in Mexico, and when arrested was

living (he told the judge) in the UK.

Perhaps

not coincidentally, Fernando Blengio-Cesena's brother, Alejandro

Blengio Cesena, works for the Federal Police in Mexico. His job?

Perhaps

not coincidentally, Fernando Blengio-Cesena's brother, Alejandro

Blengio Cesena, works for the Federal Police in Mexico. His job?

Overseeing the destruction of drugs the government confiscates in drug busts.

Another cartel ringleader, Marwan Chebli Chebli, who is Lebanese, was living in the Dominican Republic.

Then

there’s José Antonio Contreras. He's supposedly from the Dominican

Republic, but (see pic at left) he looks a little too pink to be a

native. Here's a clue: his name (Contreras) is the Spanish spelling of

the last name of a notorious Sicilian Mafia family, the Controni’s, that

have ruled Montreal’s narcotics underworld since the 1960’s.

Then

there’s José Antonio Contreras. He's supposedly from the Dominican

Republic, but (see pic at left) he looks a little too pink to be a

native. Here's a clue: his name (Contreras) is the Spanish spelling of

the last name of a notorious Sicilian Mafia family, the Controni’s, that

have ruled Montreal’s narcotics underworld since the 1960’s.

Italian

involvement in organized crime predates the Sinaloa Cartel by hundreds

of years. And there has been a substantial Lebanese and Syrian presence

in the illicit narcotics business for decades. There are several

Lebanese, and Syrian drug kingpins in Mexico, for example, whose names

are well-known in Mexico.

The demonizing of the Sinaloa Cartel serves a purpose. Consider what happened to the Medellin Cartel.

Long before it became Public Enemy No 1., the Medellin Cartel had played the same role, as the DEA’s

bogeyman, during the 70’s and 80’s, when they were responsible,

according to the DEA, for 75% of the cocaine flooding American streets.

Long before it became Public Enemy No 1., the Medellin Cartel had played the same role, as the DEA’s

bogeyman, during the 70’s and 80’s, when they were responsible,

according to the DEA, for 75% of the cocaine flooding American streets.

Yet

when the last Medellin cartel kingpin still free, Pablo Escobar, was

killed in 1992, the amount of cocaine available in the US didn’t drop by

75%.

It

didn’t drop at all. One year later, cocaine was no more difficult to

find on the streets of America than it had been while Escobar was alive.

After

Shorty Guzman and the Sinaloa Cartel have been defeated, and are no

more than a fading memory, cocaine will be as plentiful and available as

it ever was, and will continue to be re-stocked on America’s “shelves”

as efficiently as Procter & Gamble replenishes supplies of Crest

toothpaste and Charmin bathroom tissue.

Andrea Hoffman knows this. You should too.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario