Sayer Ji

Oct 12, 2025

Read, share, and comment on the X post dedicated to this story: https://x.com/sayerjigmi/status/1981002847979241734

Story at a glance

Mass Medication Crisis: Every day, millions of children are prescribed amphetamine-based drugs for ADHD—a practice that is ethically outrageous and medically reckless. ADHD stimulants like Adderall and Ritalin are essentially pharmaceutical “speed,” nearly identical in effect to illicit narcotics, handed out to developing children on an unprecedented scale.

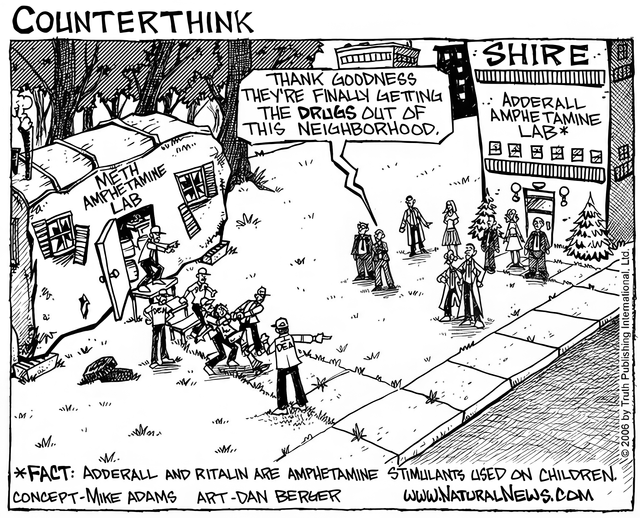

The ADHD Industrial Complex: The pathologizing of normal childhood behavior has been fueled by aggressive marketing, dubious diagnostics, and institutional complacency. An “ADHD industrial complex” of drug companies, paid psychiatrists, and advocacy groups has peddled misleading claims while suppressing dissenting voices who questioned medicating kids.

Questionable Diagnosis, Real Harm: ADHD as a diagnosis often reifies behaviors that reflect underlying issues—nutritional deficiencies, environmental stressors, trauma, or neurotoxic exposures—rather than a discrete brain disease. The side effects of stimulants range from insomnia and stunted growth to addiction and psychosis. Prescribing amphetamine-class substances to kids is a crisis, not a cure.

A Better Path Forward: Pycnogenol, an extract of French maritime pine bark, represents a scientifically validated, safe, and holistic alternative. Clinical studies show Pycnogenol improves attention and reduces hyperactivity without the dangers of stimulants. As a powerful antioxidant and anti-inflammatory, it works to restore neurological balance rather than hijacking dopamine pathways—with virtually no side effects or addiction risk.

“Giving children speed is not therapy—it’s chemical control masquerading as medicine.”

The Absurd Normalization of “Speed” in Kids

In classrooms across the country, children as young as six line up for their midday dose of Schedule II stimulants—drugs classified alongside cocaine and methamphetamine for their high abuse potential. That’s right: we are routinely giving kids pharmaceuticals that the DEA considers nearly equivalent to cocaine in how they act on the brain. Methylphenidate (Ritalin), for example, “binds to the same receptor sites in the brain as cocaine and produces effects that are indistinguishable from cocaine,” according to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration.¹ Amphetamine sulfate, the core of Adderall, is literally an amphetamine—a close chemical cousin of crystal meth. It’s “speed” by any common definition.

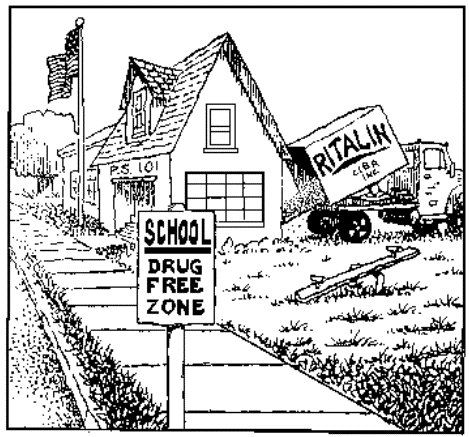

Not long ago, the idea of prescribing such drugs to millions of schoolchildren would have been unthinkable. In 1970, when reports first emerged of elementary students being given Ritalin and Dexedrine as “behavior modifiers,” public reaction was swift and angry. A prominent psychiatrist testified to Congress that “a disorder usually believed to be relatively uncommon should suddenly become a major affliction of childhood is a mystifying matter... We seem to have a plague of hyperkinetic children on our hands,” he warned.² In the New York Review of Books, one critic blasted the practice as nothing less than ”fashionable quackery.”² Yet what was once controversial quickly became commonplace. By 1990, the number of U.S. children on ADHD medication had swollen to over half a million, and it kept climbing unabated.³ Today, those early fears of a “plague” of drugged kids have materialized beyond anything imagined: over 6 million American children have been diagnosed with ADHD, and about 3.5 million of them—roughly 1 in 12 of all kids—are on stimulant medications.⁴

How did we get here? How did feeding young minds a steady diet of amphetamines become a normalized “solution”for restless behavior? The story is a case study in medicalization run amok and corporate influence on a grand scale. Pharmaceutical companies realized early on that drugs like Ritalin could be massively profitable if childhood misbehavior could be reframed as a chronic medical condition requiring long-term pharmacological management. In 1980, the American Psychiatric Association literally changed the definition of the disorder in ways that aligned perfectly with stimulant treatment. The new diagnosis of “attention deficit disorder” (later ADHD) was defined primarily by problems with sustained attention and self-control—“a definition that precisely mirrored the deficits that stimulant medications were believed to reduce,” effectively creating a “drug-induced” model of the disorder.⁵ Hyperactivity, once the core symptom, was downgraded to optional. This opened the floodgates: by broadening the diagnostic criteria, many more children’s behaviors could be labeled as pathology—and medicated accordingly.

They expanded the definition of ADHD to fit the drug. The cure came first; the disease was tailored to follow.

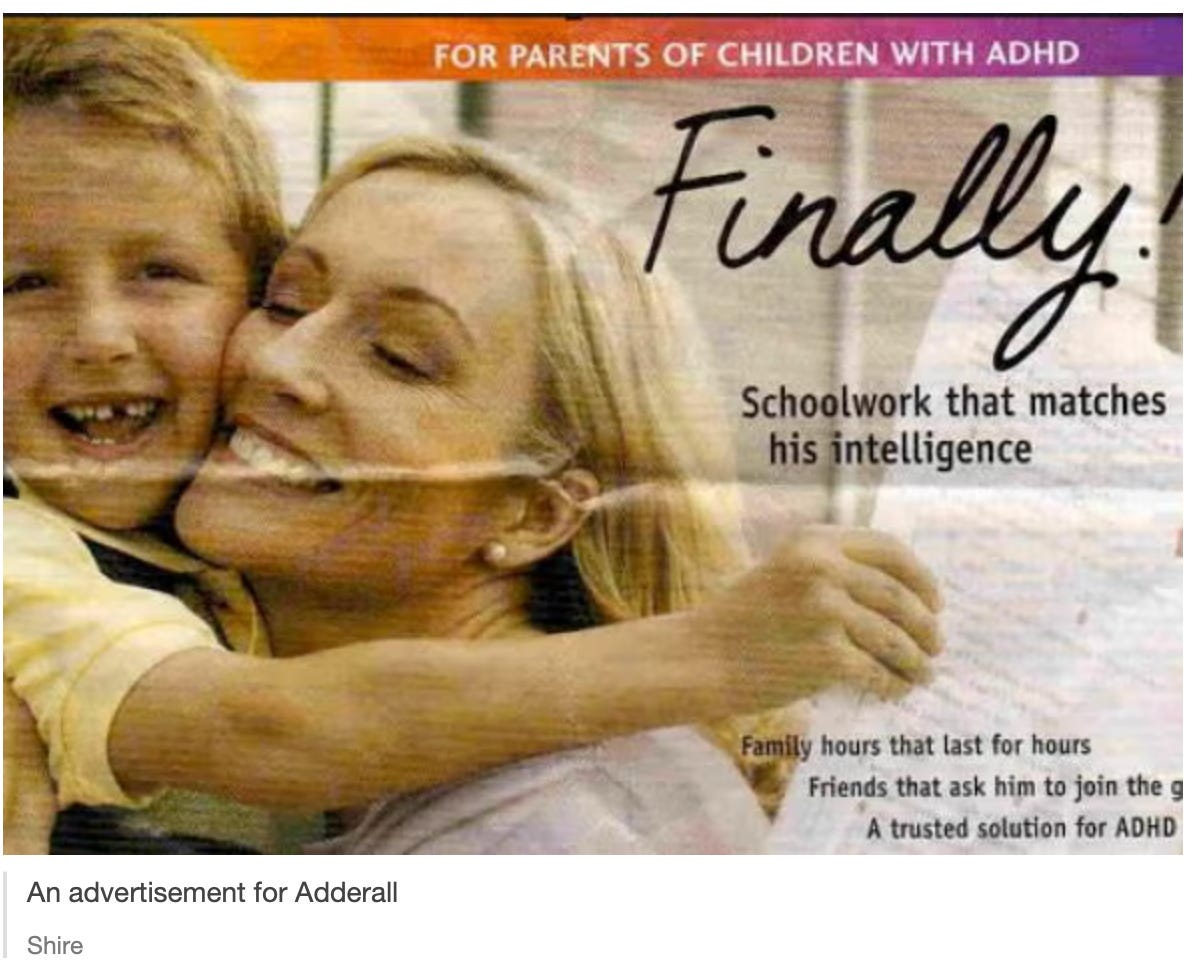

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, an ADHD marketing juggernaut steamrolled through pediatric medicine and our school systems. Drug-makers funded “educational” campaigns and parent advocacy groups to promote awareness of ADHD—conveniently emphasizing the need for medication. Perhaps the most egregious example is CHADD (Children and Adults with ADHD), a prominent nonprofit ostensibly supporting families with ADHD. CHADD has quietly received huge sums from stimulant manufacturers since its founding. By the mid-1990s, CHADD had taken over $800,000 in “educational grants” from Ciba-Geigy (maker of Ritalin) and even petitioned the DEA to relax Ritalin’s Schedule II restrictions to allow greater production.⁶ Incredibly, many parents attending CHADD meetings had no idea the group was pharma-funded and effectively acting as a marketing arm for Ritalin.⁶ At the same time, drug companies wooed doctors with paid seminars and slick journal ads. A former executive at Shire Pharmaceuticals even admitted he coined the brand name “Adderall” as a play on words for “ADD for All,” encapsulating the industry’s grand ambition to widen the market.⁷ And widen it they did—by the 2010s, ADHD medication use had exploded not only in children but in adults and college students, with pills like Adderall becoming household names (and, on campuses, black-market study aids).

The Chemical Arsenal: Ritalin vs. Adderall and the Pharma Succession Game

To understand how we arrived at today’s amphetamine epidemic in children, we need to examine the chemical differences between the two dominant ADHD drugs—and the cynical business strategy behind their alternating market dominance.

Ritalin (methylphenidate) and Adderall (mixed amphetamine salts) are both stimulants, but they work through distinctly different mechanisms:

Ritalin is a piperidine derivative that primarily acts as a dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor—it blocks the brain from reabsorbing these neurotransmitters after release, leaving more available in the synapses. First synthesized in 1944 and marketed by Ciba-Geigy (now Novartis) in 1955, Ritalin became the go-to “school drug” throughout the 1950s–1980s. It was marketed as gentler and more “medical” than amphetamines, which by then had become associated with abuse.

Adderall, by contrast, is a true amphetamine—a phenethylamine compound that doesn’t just block reuptake but actually forces the release of dopamine and norepinephrine from nerve terminals while also inhibiting their reuptake. This dual action makes it more potent. Adderall’s amphetamine salts trace back to the 1920s, originally used in products like Benzedrine inhalers and later the weight-loss drug “Obetrol.”

Here’s where the story gets interesting—and infuriating. In 1996, just as Ritalin’s patent was expiring and generic methylphenidate was flooding the market, Richwood Pharmaceuticals (later acquired by Shire) launched Adderall—a brilliant rebranding of the old Obetrol formulation, now marketed specifically for ADHD.⁸ By renaming and repackaging amphetamines for ADHD treatment, Shire positioned Adderall as a “next-generation,” longer-lastingalternative to Ritalin. The timing was no coincidence: Adderall’s rise was directly orchestrated to fill the vacuum left by Ritalin’s patent expiration, offering a new proprietary stimulant that doctors could prescribe under patent protection—and that pharmaceutical reps could aggressively market.

The strategy worked spectacularly. By the late 1990s and early 2000s, especially after the release of Adderall XR(extended-release) in 2001, Adderall became the dominant ADHD drug, perceived as more potent and convenient. Ritalin became somewhat “old-school,” though new extended-release methylphenidate formulations (Concerta, Metadate) attempted to compete. Today, amphetamine-based stimulants (Adderall, Vyvanse) dominate U.S. ADHD prescriptions, while methylphenidate-based drugs still hold significant market share, particularly for younger children.

The lesson? Adderall didn’t replace Ritalin because it was scientifically superior—it replaced it because of patent economics and marketing muscle. The shift was as much about corporate profit-seeking as any medical advancement. Both drugs manipulate the same neurotransmitter systems; both carry serious risks; both are Schedule II controlled substances. The pharmaceutical industry simply found a way to keep the gravy train running by cycling through chemical variations and brand names, all while millions of children became dependent on these substances. This is the “pharma succession game”—and children’s brains are the playing field.

Pathologizing Childhood: The ADHD “Disease” That Isn’t

Lost in this rush to medicate was a fundamental question: What if ADHD isn’t a clear-cut disease at all? The diagnosis itself is based on a checklist of behaviors—inattention, impulsivity, hyperactivity—that are frustrating to adults but hardly uncommon in childhood. By turning a spectrum of normal (if challenging) behaviors into a medical disorder, we have pathologized childhood itself. And we’ve ignored the possibility that those behaviors might be symptoms of various underlying issues, not evidence of a singular brain malfunction.

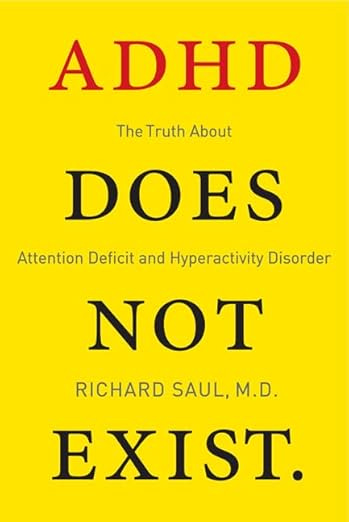

Leading critics have long argued that ADHD as a standalone disorder lacks scientific validity. “ADHD has no proven biological marker and no definitive test; it’s a construct that lumps together kids who may simply be bored, traumatized, or immature,” they note. Psychiatrist Peter Breggin famously asserted that the diagnosis and drug treatment of ADHD are essentially “a means of social control—a way to suppress the behaviors of unruly children” rather than to heal a medical condition.⁹ From another angle, physician Richard Saul—author of ADHD Does Not Exist—reviewed dozens of cases and concluded that every child he saw labeled ADHD actually had some other root cause: from poor eyesight and lack of sleep to learning disabilities or emotional trauma. All the many symptoms rolled into “ADHD,” he argues, “can better be accounted for by some twenty other conditions... ADHD is being falsely diagnosed and wrongly treated in every case because it is not a separate disorder at all.”⁹ In other words, the label “ADHD” often serves to paper over the real issue.

Consider a child who can’t focus in class. Is it because he has a Ritalin-deficiency “brain disease,” or could it be that he’s sleep-deprived, eating a junk food diet, or anxious from turmoil at home? Research has linked ADHD-type symptoms to high lead levels, prenatal toxin exposure, allergies to food additives, nutrient deficiencies (like low iron, zinc or magnesium), and early childhood trauma. Kids living with chronic stress or instability may become impulsive and distracted—a normal human response to abnormal life conditions. Yet instead of addressing these root causes (better nutrition, counseling, safer environments), our system is geared to speed-diagnose and medicate. A ten-minute pediatric consult and a quick prescription of stimulants have become the default “solution” for a struggling child.

Labeling these children as mentally disordered and drugging them can be profoundly harmful. It sends a message that something is fundamentally “wrong” with them—that their brain is broken, needing daily chemical fixes. It also excuses us from examining what might be “wrong” in the child’s world. Overcrowded classrooms, lack of play and exercise, unrealistic academic expectations, trauma and poverty—all get swept under the rug when we pin everything on the child’s neurotransmitters. The ADHD diagnosis tells us nothing about cause—it’s a description reified into a disease. Meanwhile, the actual causes of a child’s inattentiveness, be it chaotic home life or malnutrition, go unaddressed.

The psychiatric-pharmaceutical complex has been only too happy to promulgate the idea of ADHD as a clear-cut neurobiological illness—“a chemical imbalance in the brain”—despite a lack of proof. Psychiatrists in the pay of drug companies tour the country showing parents colorful brain scans purportedly showing ADHD in action, even though no such diagnostic scan exists.¹⁰ The authority of the white coat and the promise of a pill-based quick fix have convinced many families that medication is not just an option but the only responsible option. Meanwhile, alternative viewpoints are marginalized. If a teacher or doctor suggests trying behavioral interventions or nutritional changes before meds, they risk being seen as not up-to-date or even negligent. The result? Nearly 15% of high school-age boys in America have been labeled ADHD, and the majority are on drugs.⁴ In some school districts, stimulant medication has practically become a rite of passage for active young boys—an outrageous development that one former NIH director decried as a “national disaster of dangerous proportions.”

We’ve medicalized boyhood mischief and childhood exuberance—and sold it by the pill.

The Dark History: Profit, Propaganda, and Suppression of Dissent

The trajectory of ADHD treatment over the past few decades reads like a cautionary tale of regulatory capture and marketing masquerading as science. Pharmaceutical corporations, smelling blockbuster profits, worked systematically to shape the narrative and silence opposition. They found willing collaborators among certain academic psychiatrists, who were handsomely funded to produce research, treatment guidelines, and even new “diseases” that supported expanded drug use. As investigative journalist Alan Schwarz has documented, an “ADHD industrial complex” of drug makers, doctors, advocacy groups, and advertisers peddled misleading claims and seductive promises to the public.⁷ Parents were bombarded with messages that ADHD drugs were benign, even “safer than aspirin,” and that untreated ADHD would doom their child to car crashes and prison. This fear-based marketing, combined with glossy portrayals of medicated kids transformed into star students, drove panicked parents into pediatricians’ offices demanding a pill.

Meanwhile, dissenting voices were often drowned out or discredited. The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration itself grew concerned by Ritalin’s overuse and convened conferences in the 1990s to warn of its cocaine-like properties—but those findings got little traction against pharma’s PR juggernaut. Professionals who spoke up about overdiagnosis or advocated non-drug approaches often found themselves sidelined. When a PBS documentary in 1995 questioned CHADD’s pharma funding and the explosion of ADHD meds, CHADD and drug companies attacked it as “one-sided” and tried to reassure the public there was no conflict of interest.¹¹ Lawsuits filed by parents in the early 2000s alleged that manufacturers of Ritalin conspired with the American Psychiatric Association to “create” ADHD as a massively profitable market. (Those suits were eventually dismissed, but they underscore the level of public distrust in how ADHD came to be so pervasive.)

It’s instructive to note how regulatory authorities largely abdicated their responsibility during this boom. The FDA continued approving new long-acting stimulant formulations and allowed advertising that downplayed risks. The Centers for Disease Control and professional bodies focused on “awareness” of ADHD but not on curbing over-prescription. Even the American Medical Association concluded in a 1997 report that there was “little evidence” of widespread overdiagnosis—a claim wildly at odds with the reality unfolding in classrooms.¹² In short, the institutions meant to protect children’s health instead protected the interests of Big Pharma.

And what have been the consequences? For an industry, billions in revenue—Adderall and Concerta and their ilk consistently rank among the most-prescribed (and profitable) drugs in America. For society, a generation of youth dependent on controlled substances and an epidemic of stimulant misuse on college campuses. For the children themselves, the costs are immeasurable: childhoods spent medicated, potential creativity and individuality stifled, and very real physical and psychological side effects (which we’ll examine next). This grand experiment of drugging kids into compliance is morally untenable. It demands not only scrutiny, but a full-scale course correction.

Stimulant Casualties: High Risks for Young Minds

Amphetamine-based medications are often euphemistically called “focus pills” or “study drugs,” but let’s call them what they are: powerful psychostimulants that manipulate brain chemistry in blunt fashion. They jack up dopamine and norepinephrine levels, inducing a temporary state of hyper-focus—at the cost of disrupting the brain’s natural regulatory balance. For some children, this pharmacological jolt can indeed produce short-term improvements in sitting still or completing rote tasks. But the illusion of normalcy comes with a heavy price.

Physically, stimulant side effects are rife. Insomnia, jitteriness, headaches, and stomach pains are common complaints. Many kids on ADHD meds experience loss of appetite and significant weight loss, as if chronic amphetamine use were a legitimate diet plan for growing bodies. The drugs can also suppress height growth; research has found that children medicated long-term may end up an inch or two shorter on average than their unmedicated peers. More alarming are cardiovascular and neurological risks: stimulants raise heart rate and blood pressure, and in rare cases have precipitated heart attacks or strokes in young people with undetected cardiac issues. Tics and Tourette’s syndrome can be triggered or worsened by these medications, indicating the drugs’ destabilizing effect on neural circuits.

Psychologically, the impact can be even more disturbing. Stimulants artificially push dopamine levels high, similar to how cocaine does, which can lead to mood swings, aggression, and even psychotic symptoms in vulnerable individuals. A large study in 2019 confirmed that adolescents and young adults treated with Adderall had twice the risk of developing psychosis (hallucinations, delusions) compared to those on other ADHD meds.¹³ We are essentially playing roulette with children’s mental stability when we hand out amphetamines so freely. Dependence and addiction are also real concerns. Tolerance can build up over time, leading to higher doses. Many teens learn they can crush and snort their ADHD pills for a stronger “high,” or mix them with other substances—a dangerous gateway to recreational drug abuse. The U.S. DEA reports thousands of cases each year of methylphenidate and amphetamine misuse or trafficking, often originating from school prescriptions.¹ The idea that giving a child a prescription stimulant will prevent future drug abuse (a claim some have made) is a cruel irony; in fact, childhood stimulant exposure may prime the brain for seeking chemical kicks and normalize the idea that one needs pills to function.

Even when used as directed, these drugs can blunt a child’s spirit. Parents have described kids on Ritalin or Adderall as “zombie-like”—subdued, emotionless, not quite themselves. Is the ability to sit still worth the loss of spontaneity and joy? Teachers might prefer a compliant class, but at what cost to the child’s well-being? We must ask: What message are we sending to a child when we respond to their energy or distraction with a controlled substance? We teach them that their natural self is defective and must be chemically corrected daily. We risk turning normal developmental variations into chronic patienthood.

After years or decades on stimulants, no one truly knows the long-term consequences on the developing brain. The oldest “Ritalin generation” is now in their 30s and 40s; some speak of grappling with dependence, lingering depression, or cognitive fog after years of riding the roller coaster of stimulant use and withdrawal. The lack of longitudinal research is glaring—we essentially authorized a vast experiment on children without waiting to see the eventual outcomes.

It bears repeating: we have been giving kids drugs nearly indistinguishable from cocaine and meth, expecting only benefits and minimal fallout. That is a degree of hubris and recklessness that future generations may judge harshly. But all is not hopeless—because even as we expose this crisis, we can also highlight a better way forward.

Pycnogenol: A Gentle and Holistic Alternative to Stimulants

Imagine if there were a remedy for attention difficulties that didn’t require turning kids into de facto amphetamine users—a remedy that worked with a child’s body to restore balance, rather than overriding it. The good news is such alternatives exist, and one of the most promising is Pycnogenol.

Pycnogenol (pronounced pick-NAW-jen-all) is a natural plant extract from the bark of the French maritime pine tree. Far from being fringe folk medicine, Pycnogenol is a well-researched nutraceutical: it contains a rich blend of procyanidins, bioflavonoids, and organic acids with potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. For decades, Pycnogenol has been studied for various health benefits—from improving circulation and skin health to boosting cognitive function. In the context of ADHD, Pycnogenol offers a multi-faceted, nourishing approach to healing the underlying issues that can cause inattentiveness and impulsivity.

How does it work? Unlike stimulants that simply flood the brain with dopamine, Pycnogenol operates in a modulatory, protective fashion. It scavenges harmful free radicals and reduces oxidative stress in the nervous system. (Notably, children with ADHD have been found to have elevated markers of oxidative damage, indicating that brain inflammation or toxin exposure could be contributing to symptoms.) In one study, just one month of Pycnogenol supplementation normalized the antioxidant levels in children with ADHD and significantly reduced a marker of DNA oxidative damage.¹⁴ This suggests Pycnogenol helps remedy an underlying imbalance rather than just paper over symptoms.

Pycnogenol also aids the neurochemical balance more gently: research shows it can regulate levels of stress hormones and neurotransmitters toward normal ranges. For instance, a European trial found that a month of Pycnogenol brought down elevated adrenaline and noradrenaline levels in ADHD kids—a sign of calming an over-stimulated system—while also slightly increasing dopamine, the focus neurotransmitter, but without the roller-coaster spikes caused by stimulants.¹⁵ In effect, Pycnogenol nudges the brain toward equilibrium instead of yanking it into overdrive.

Furthermore, Pycnogenol addresses several contributing factors to attention problems: It limits the production of excess glutamate, an excitatory neurotransmitter that in high amounts can cause hyperactivity and even neuron damage.¹⁶ It helps reduce inflammation and histamine release, which is relevant since some kids become hyperactive due to food sensitivities and allergic reactions.¹⁶ It strengthens the blood-brain barrier, potentially keeping environmental toxins like heavy metals out of the brain.¹⁶ It even modestly improves cerebral blood flow, aiding oxygen and nutrient delivery to brain cells.¹⁶ In short, Pycnogenol works holistically: healing and protecting the brain’s environment so that concentration and behavior can improve naturally.

Crucially, these benefits translate to real-world improvements. Clinical studies on Pycnogenol for ADHD are extremely encouraging. In a gold-standard randomized, placebo-controlled trial, 61 children with ADHD were given Pycnogenol (1 mg per kg body weight) or placebo for 4 weeks. The results were striking: Pycnogenol caused a significant reduction in hyperactivity and improved attention, concentration, and coordination compared to placebo, as rated by teachers and parents.¹⁷ The children’s symptoms notably relapsed after Pycnogenol was discontinued, underscoring that it was the Pycnogenol making the difference, not a placebo effect. The researchers concluded that Pycnogenol is a promising “natural supplement to relieve ADHD symptoms” in children.¹⁷

Another trial, published in 2022, compared Pycnogenol head-to-head with the standard drug methylphenidate over 10 weeks.¹⁸ The findings? Pycnogenol was nearly as effective as the stimulant in reducing teachers’ ratings of hyperactivity and inattention—but with virtually none of the side effects. The Pycnogenol group saw improvements build up gradually over several weeks (this supplement isn’t a harsh quick fix, but a gentle rebuilder). By week 10, teachers reported a ~29% overall ADHD symptom reduction on Pycnogenol, versus ~45% on methylphenidate—a meaningful benefit, if slightly less immediate than the drug’s effect. Parents’ ratings showed smaller improvements, which may reflect that Pycnogenol’s effect is most noticeable in structured settings like school. Critically, however, the children on Pycnogenol had almost no adverse effects, while the Ritalin group experienced five times more side effects.¹⁸ Where the stimulant caused appetite loss and weight loss in many kids, those on Pycnogenol had no appetite issues and continued to grow and eat normally.¹⁸ No insomnia, no elevated heart rate, no emotional blunting were observed with the pine bark extract. It’s a night-and-day contrast: one treatment clouds a child’s physiology in side effects, the other appears remarkably safe and well-tolerated.

Pycnogenol didn’t drug children into obedience—it helped restore their balance.

Beyond these trials, multiple other studies reinforce Pycnogenol’s benefits for ADHD. Research in Slovakia found that Pycnogenol use led to higher levels of glutathione (the body’s master antioxidant) in children, and a corresponding drop in oxidative stress by-products, correlating with improved attention scores.¹⁹

Another small study noted better visual-motor coordination and concentration after a month on Pycnogenol.¹⁷ Even in healthy students, Pycnogenol supplementation for 8 weeks improved memory, focus, mood, and cognitive function—showing it can enhance mental performance without any disorder present.¹⁶ Significantly, addiction or habit-formation is not a concern with Pycnogenol. It does not act on the brain’s reward pathway in the intense way amphetamines do; you can’t get “high” from pine bark, and there’s no withdrawal syndrome when stopping it. The worst one might expect is an upset stomach in a minority of users, or slight dizziness in rare cases—and even those effects are uncommon. In over 40 years of research and use, Pycnogenol has amassed a solid safety record with no serious adverse events attributed to it.¹⁷,¹⁸

It feels almost absurd to compare: on one side, a class of drugs that require DEA control, can stunt growth, spark psychosis, and hook kids into dependency; on the other, an extract from a tree that quietly helps the brain heal and function better. Yet the latter remains relatively unknown to mainstream medicine and rarely offered to parents as an option. Why? Follow the money: Pycnogenol can’t be patented (it’s a natural product), and a course of pine bark extract capsules costs a fraction of brand-name amphetamines. No wonder it isn’t heavily advertised in medical journals or pushed by pharmaceutical reps. In a profit-driven system, a humble plant remedy—no matter how effective—struggles to compete with trillion-dollar drug brands.

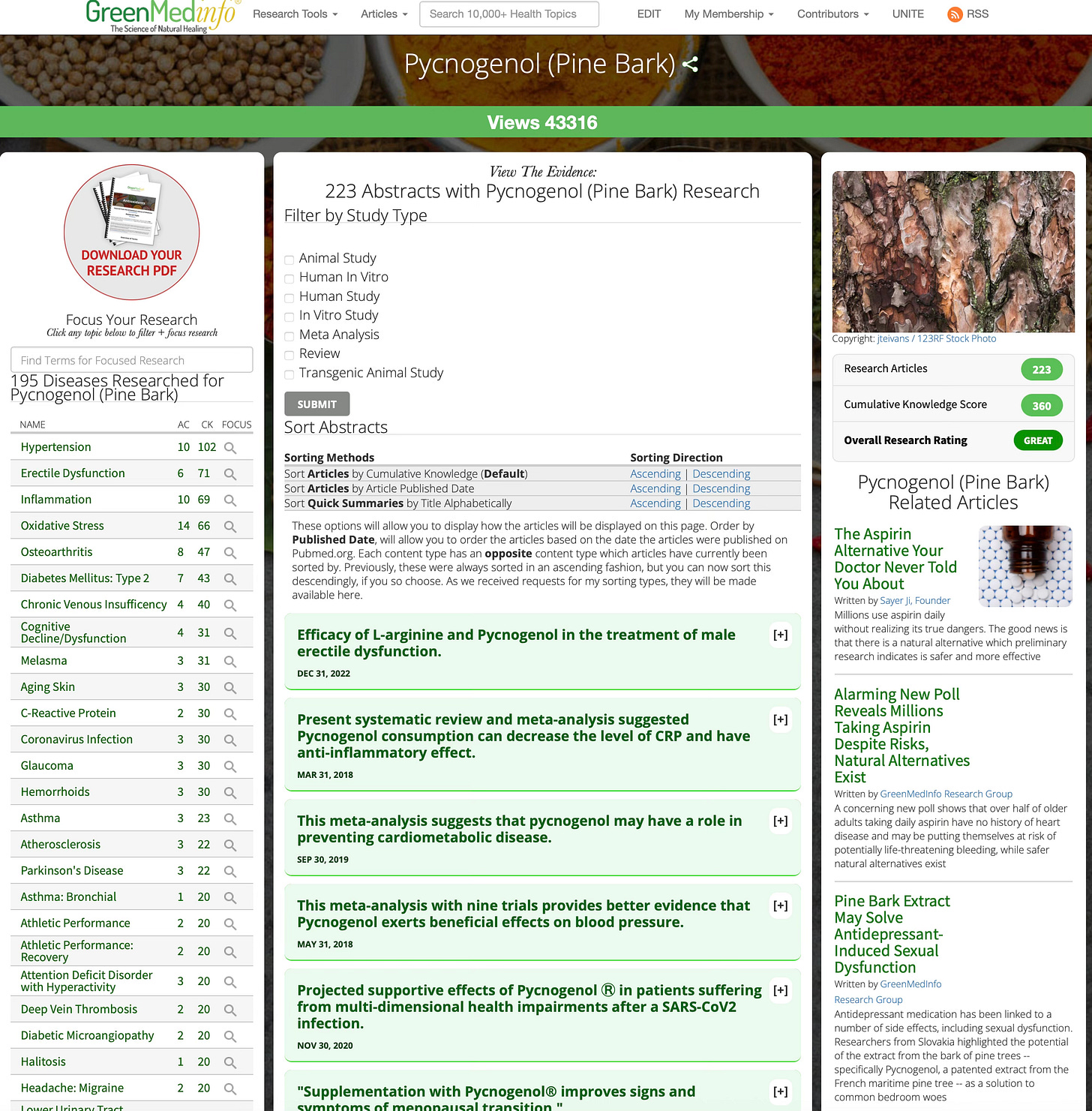

Pcynogenol has a wide range of ‘side benefits,’ with research indicating its potential therapeutic value in almost 200 different conditions or symptoms

Restoring Children’s Futures: From Crisis to Cure

It is time for a paradigm shift. We must recognize that medicating millions of kids with what are essentially low-dose amphetamines is a public health crisis. It didn’t happen by accident; it was engineered by entities that put profit above children’s well-being. But we—parents, educators, ethical professionals—can choose a different path forward.

First, we need to reclaim the narrative of childhood behavior. Children, especially boys, are naturally rambunctious, curious, and at times inattentive. These traits are not diseases. Yes, some children struggle more with focus and impulse control, and they deserve help—but help should start with understanding why they struggle. Let’s invest in finding the real causes: Is the child bored by a one-size-fits-all curriculum? Are sensory issues or an undiagnosed learning disability hindering them? Could counseling help address anxiety or trauma that underlie their restlessness? Is the child’s diet full of sugar and artificial dyes that wreak havoc on mood and concentration? These questions take more time to explore than writing a prescription, but the answers can lead to true healing.

We also must demand honesty about the drugs’ harms. The psychiatric establishment cannot continue to minimize or ignore the downsides of stimulant therapy. Innocent children cannot give informed consent to the long-term risks they are being exposed to. It falls on adults to err on the side of caution. Physicians should be educated about nutraceuticals like Pycnogenol, omega-3 fatty acids, magnesium, and other evidence-backed interventions for attention—and offer them as first-line options before considering controlled substances. Schools should adopt more inclusive practices: more recess and physical activity (proven to improve attention), smaller class sizes, and behavioral supports that don’t rely on pharmacology.

Importantly, the alliance of parents and enlightened health professionals will be key. Parents should feel empowered to question an ADHD diagnosis and seek a second opinion—or a third. They should not be shamed for wanting to try natural alternatives or behavioral strategies. The current system often pressures parents with ultimatums (”medicate your child or he’ll fall behind / be suspended”), which is unethical and unacceptable. Instead, imagine a system where a parent who says “I’m worried about side effects; are there other options?” is met with a collaborative discussion of things like Pycnogenol, dietary changes, parenting strategies, tutoring—a whole-person plan for the child.

Pycnogenol is not presented here as a magic bullet or the single answer for every child. But it embodies the kind of approach we need: one that works with biology, not against it; that prioritizes safety and nourishment over instant gratification; that addresses root causes (oxidative stress, nutrient deficits, etc.) rather than just symptoms. The fact that Pycnogenol can achieve comparable improvements to Ritalin in some trials¹⁸ speaks volumes—it means many kids labeled with ADHD perhaps never needed amphetamines in the first place. Their brains weren’t “chemically deficient” in stimulants; they were craving support and protection, which an extract from a tree was able to provide.

In closing, we must state clearly: prescribing amphetamines to children on a mass scale is a moral catastrophe. It will be remembered as a shameful era in medicine—an era we must hasten to end. We have drugged a generation for convenience and profit, but we can stop now. We can declare: No more. No more will we sacrifice children’s potential and health at the altar of Big Pharma’s quick fix. No more will we accept that managing a rowdy classroom justifies giving little kids the same class of drugs that fueled the 1960s speed epidemic.

A better way is within reach. By recognizing ADHD for what it often is—a set of symptoms with varied causes—we open the door to individualized, compassionate care. By embracing remedies like Pycnogenol and other holistic measures, we can help children thrive without compromising their growth or spark. Let’s return childhood to the children, free from the cloud of amphetamines. The crisis is now; the cure is our courage to change course.

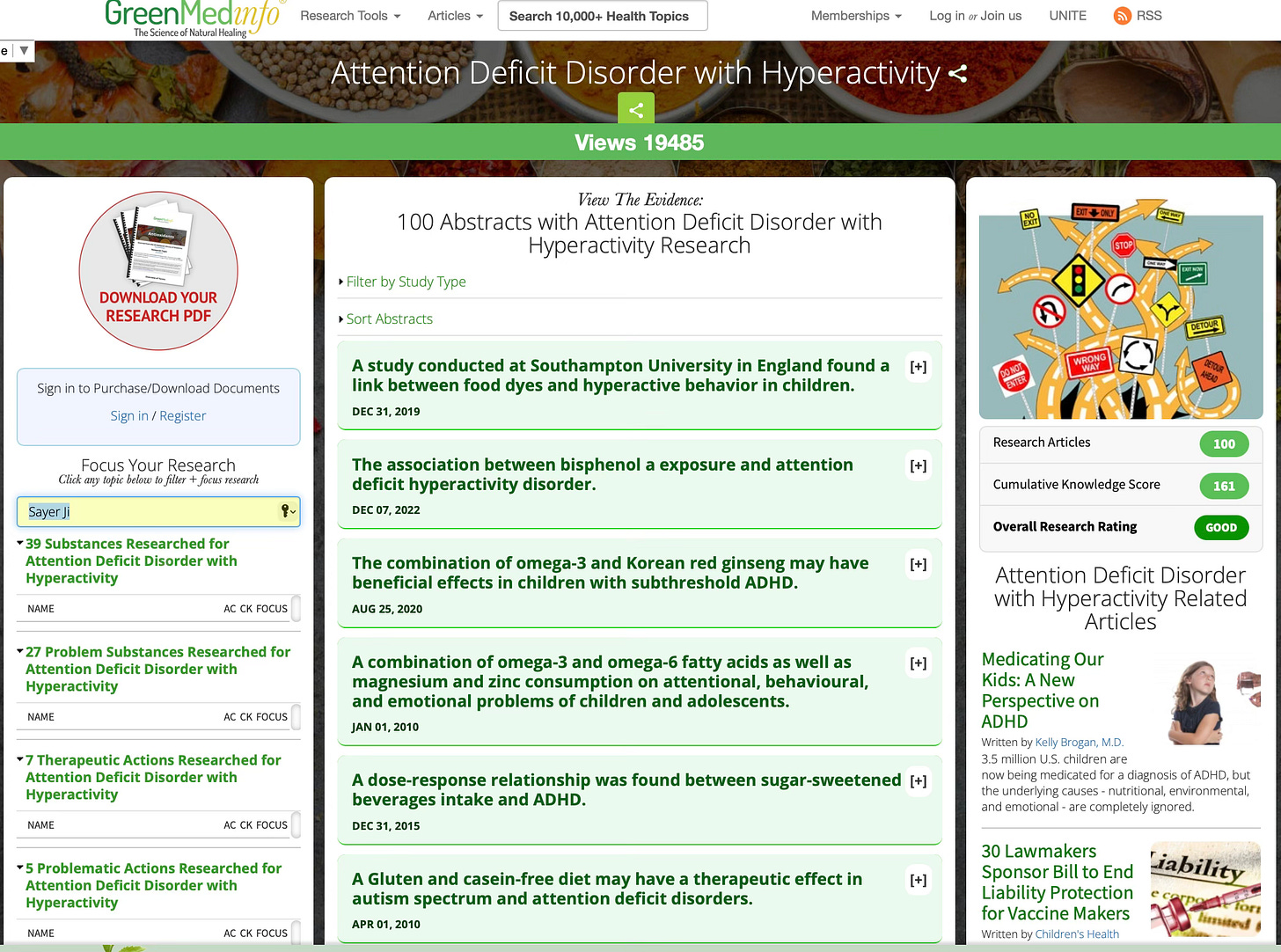

To learn more about natural approaches to ADHD, view our database dedicated to the subject on Greenmedinfo.com.

Editor’s note: This story is part of a larger investigation into the pharmaceutical colonization of childhood—from amphetamines to antidepressants to vaccines. In an upcoming piece, I’ll explore the origins of the vaccine-autism controversy and what the science actually shows when we look beyond industry-funded narratives.

References

U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. “Methylphenidate.” Drug Fact Sheet, DEA Diversion Control Division, August 2025. https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/drug_chem_info/methylphenidate.pdf.

Davis, Joseph E. “ADD for All: On Big Pharma, Overdiagnosis, and the Questions Unasked about Medicalization.” The New Atlantis, Spring 2017. https://www.thenewatlantis.com/publications/add-for-all.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Schnaiberg, Lynn. “TV Show Links ADD Support Group, Drug Company.” Education Week, October 18, 1995. https://www.edweek.org/education/tv-show-links-add-support-group-drug-company/1995/10.

Davis, “ADD for All.”

Ibid.

Ibid.

Cornwall, Michael, PhD. “Why Parents Give Amphetamines and Other Risky Psychiatric Drugs to the Children They Love.” Mad in America, June 1, 2016. https://www.madinamerica.com/2016/06/why-parents-give-prescription-amphetamines-and-other-risky-psychiatric-drugs-to-the-children-they-love/.

Davis, “ADD for All.”

Moran, Lauren V., et al. “Psychosis with Methylphenidate or Amphetamine in Patients with ADHD.” New England Journal of Medicine 380, no. 12 (2019): 1128–1138. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1813751.

“Study Finds Pycnogenol® May Be Effective for Managing Pediatric ADHD Without Side Effects Commonly Associated With Pharmaceuticals.” BioSpace press release, October 19, 2022. https://www.biospace.com/article/releases/study-finds-pycnogenol-may-be-effective-for-managing-pediatric-adhd-without-side-effects-commonly-associated-with-pharmaceuticals/.

Dvořáková, M., et al. “Urinary Catecholamines in Children with ADHD: Modulation by a Polyphenolic Extract from Pine Bark (Pycnogenol).” Nutritional Neuroscience 10, no. 3-4 (2007): 151–157. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18074301/.

Greenblatt, James, MD. “How Pine Bark Extract (Pycnogenol) Can Help Regulate ADHD Symptoms.” Psychiatry Redefined, April 11, 2022. https://www.psychiatryredefined.org/how-pine-bark-extract-pycnogenol-can-help-regulate-adhd-symptoms/.

Trebatická, Jana, et al. “Treatment of ADHD with French Maritime Pine Bark Extract, Pycnogenol.” European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 15, no. 6 (2006): 329–335. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16699814/.

“Study Finds Pycnogenol® May Be Effective,” BioSpace.

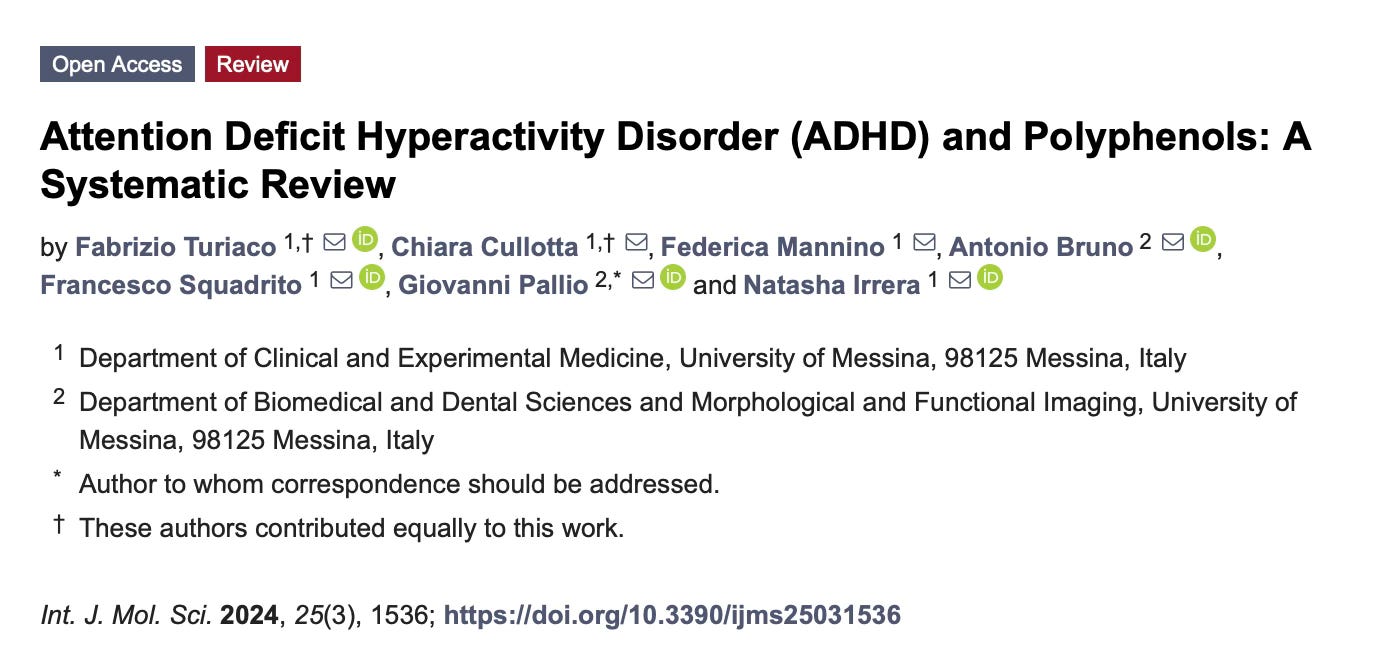

“Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and Polyphenols: A Systematic Review.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences 25, no. 3 (2024): Article 1536. https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/25/3/1536.

![Kids! Just say No to Drugs... Did you take your Ritalin Today, Kids?". Cartoon from Chicago Tribune c. 2010 [War on Drugs, Paediatric Psychopharmacology] : r/PropagandaPosters Kids! Just say No to Drugs... Did you take your Ritalin Today, Kids?". Cartoon from Chicago Tribune c. 2010 [War on Drugs, Paediatric Psychopharmacology] : r/PropagandaPosters](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!z_Nu!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F209a614f-5c67-49bb-8521-3810132f3e72_1080x873.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario