For over three decades, I have been deeply immersed in reflecting on the role of melanin in human physiology and our origin story, engaging in ongoing dialogue with scientific colleagues, mentors, and skeptics alike. This fascination with our body's hidden regenerative capacities ultimately led me to write my book REGENERATE: Unlocking Your Body's Radical Resilience Through the New Biology, where I first explored how melanin might play a far more profound role in human health than conventionally understood. This piece represents a synthesis of some of the most exciting discoveries and conceptual shifts emerging from those conversations and investigations—and totally new ones that surprised even me as far as their far-reaching implications. It is also the first in a series of essays I'll be publishing on the New Biophysics of Light and Humanity’s True Origins. I am excited to finally share this summary.

Prologue: Light in the Dark

On the ruined walls of Chernobyl's reactor, something strange was found growing. A decade after the meltdown, scientists noticed a black fungus thriving in the radiation-soaked darkness. It wasn't feeding on rubble or radioactive minerals, but seemingly on the radiation itself. This melanized fungus (Cryptococcus neoformans) grew faster under gamma rays – a phenomenon dubbed "radiosynthesis," as if it were performing a kind of fungal photosynthesis with ionizing radiation. The key was melanin, the very same pigment that darkens human skin. Melanin appeared to be harvesting energy from deadly rays and turning it into life.

Such a claim sounds like science fiction: a pigment that eats radiation. Yet this discovery was among the early hints (the first being the discovery of melanized radiation-eating bacteria in 1956), that melanin might be far more than a biological coloring agent. It set the stage for a radical rethinking of what this ubiquitous pigment does – not just in fungi, but in us. That black fungus at Chernobyl is a vivid, almost cosmic image. It calls to mind an ancient intuition: that life, even in darkness, somehow seeks the light.

As bizarre as "radiation-eating" fungi are, they form part of a broader story unfolding over the past ten or so years – a story of scientists rediscovering melanin as a bioenergetic engine. It's a tale of bold ideas and personal obsessions, of skepticism slowly yielding to curiosity, and of science converging with themes that feel almost philosophical. This journey from vision to validation has challenged one of biology's core assumptions: that animals (ourselves included) cannot directly harness the energy of light for metabolism. What if that assumption was only mostly true? What if, hidden in plain sight (or rather in darkness), there was a mechanism by which our bodies capture light and turn it into useful energy?

The prospect is both profound and strangely poetic – that within our cells, a little bit of "sunlight alchemy" might be happening, quietly fueling our lives. To appreciate how revolutionary this idea is, we must first understand how melanin was traditionally viewed, and what curiosities hinted at its secret power.

The Mystery of Melanin

Melanin is familiar to anyone who's seen their skin tan in summer or admired the inky eye of a bird. Biologists have long categorized melanin as a pigment – essentially a biological color whose main job is to absorb light. In humans and many animals, melanin in the skin, hair, and eyes protects against the sun's ultraviolet (UV) rays, preventing DNA damage. As early as 1820, scientists had concluded that melanin was simply a "sunscreen" in our bodies. For two centuries, this idea stuck: melanin as nature's UV filter, nothing more.

On the surface, it made perfect sense. Dark skin evolved in high-UV environments to guard against sunburn and skin cancer; the melanin in our retina shields sensitive photoreceptors from excess light; melanin in fur or feathers provides camouflage and absorbs warmth. Melanin's role seemed straightforward – a protective dye in the great canvas of biology.

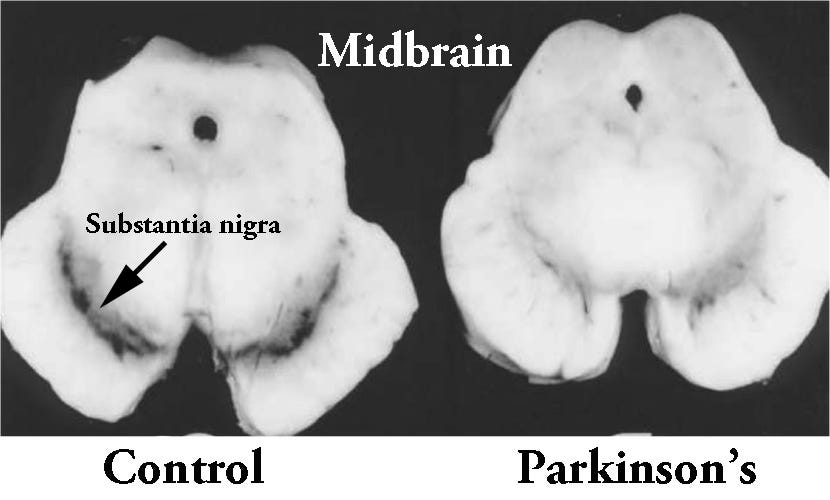

Yet even as textbooks dutifully repeated melanin's sunscreen status, scientists kept stumbling on puzzles that didn't fit the simple story. For one, melanin pops up in places where sunlight scarcely shines. Consider the human brain: certain neurons in the deep brain (the substantia nigra and locus coeruleus) are loaded with neuromelanin, giving these regions a dark hue. Why would brain cells – tucked inside the skull – bother to produce a UV-blocking pigment? The inner ear is another enigma: the cochlea has melanocytes (pigment cells), and their dysfunction can cause hearing loss. Again, no sunshine reaches there. Even stranger, melanin is found in the heart valves of some animals and the lungs of certain seabirds. These "internal melanized sites" not obviously subject to light have puzzled researchers for years. Could melanin be doing something else there?

Laboratory observations added to the mystery. In one experiment, skin cells rich in melanin were found to contain far fewer mitochondria – the tiny organelles that generate ATP energy – than their non-pigmented counterparts, yet they grew and developed just as well. In these heavily melanotic cells, mitochondrial number dropped a whopping 83%, and respiration (the usual oxygen-burning energy process) was 30% lower, without impairing cell growth. It was as if the melanin was somehow compensating for the lost mitochondria.

Clinicians also noted paradoxes: melanin in the skin reduces UV DNA damage (protective), but an abundance of melanin can correlate with melanoma (cancer) risk; neuromelanin in the brain might be protective in some ways but is lost in Parkinson's disease, possibly contributing to degeneration. Melanin, the pigment, was behaving less like a static shield and more like a dynamic player – one with a dual nature that scientists didn't yet fully grasp.

Such anomalies prompted a few intrepid thinkers to ask uncomfortable questions. Was it possible that melanin had a metabolic function – that it could, under the right conditions, act as an energy source or catalyst for life's processes? This notion cuts against the grain of classic biology. After all, one of the defining traits of animals is that, unlike plants, we must consume external food for energy; we don't just sit in the sun and grow (at least, that's what we were taught). "Animal inability to utilize light energy directly has been traditionally assumed," wrote one researcher in 2008. It was practically dogma that only photosynthetic organisms (plants, algae, some bacteria) could turn light into biochemical energy.

And yet, those recurring hints – pigments in dark places, cells managing with fewer mitochondria – suggested a provocative alternative: maybe evolution didn't completely forsake the idea of animal cells harnessing light. Maybe it just hid it in a different form.

Visionaries and a Radical Hypothesis

In the mid-2000s, a few scientists began to voice the idea that melanin might be an "unrecognized bioenergetic molecule." They were, in effect, proposing a form of animal photosynthesis, with melanin playing the role analogous to chlorophyll. One of the early proponents was Geoffrey Goodman, who published a speculative paper in 2008 titled "Melanin directly converts light for vertebrate metabolic use".

It appeared in the journal Medical Hypotheses – a venue known for outside-the-box ideas – and it laid out Goodman's case that melanin could capture electromagnetic radiation and make it biologically useful¹.

Goodman pointed to that avian puzzle called the pecten oculi: a comb-like, pigmented organ in bird eyes. The pecten is rich in melanin and blood vessels and is much enlarged in birds that fly long distances. Its true function was unknown, but Goodman hypothesized that the pecten might "help cope with energy and nutrient needs under extreme conditions, by a marginal but critical, melanin-initiated conversion of light to metabolic energy, coupled to local metabolite recycling". In plain language, he was saying the bird's eye might house a tiny solar panel (melanin-rich pecten) providing an extra trickle of fuel to the retina or brain during the marathon of migration.

This was a bold leap, but it elegantly explained why a high-flying goose or hawk would have a big pigmented eye-organ: fighting gravity, hypoxia, and hunger on a long flight, any extra energy – even a small boost from absorbed light – could be life-saving.

Goodman didn't stop at birds. He drew a parallel to human evolution. Humans are oddly hairless compared to other primates, and we developed very dark skin in equatorial Africa. Traditional explanations for hairlessness include temperature regulation (sweating better) and reducing parasites, while dark skin protects from UV. But Goodman mused there might be another benefit: with less hair and more melanin in our skin, perhaps early humans could perform a bit of "photomelanometabolism" – using melanin to convert sunlight into metabolic energy. Even if each square inch of skin produced only a tiny amount of extra energy, the total body surface might yield enough to matter, especially for an energy-hungry organ like the brain. He suggested this could have "enabled a sharply increased development of the energy-hungry cortex" in our ancestors and given a survival edge in famine or endurance situations.

It was a fascinating idea: that shedding fur and soaking up the sun might have literally powered our evolving brains. It cast melanin as a driver in human origins, not just a passive trait. Goodman admitted the idea was heuristic – more a thought experiment to stimulate research than a proven fact. But he ended with a provocative statement that captured the spirit of this emerging paradigm: "there is more in melanin than meets the eye".

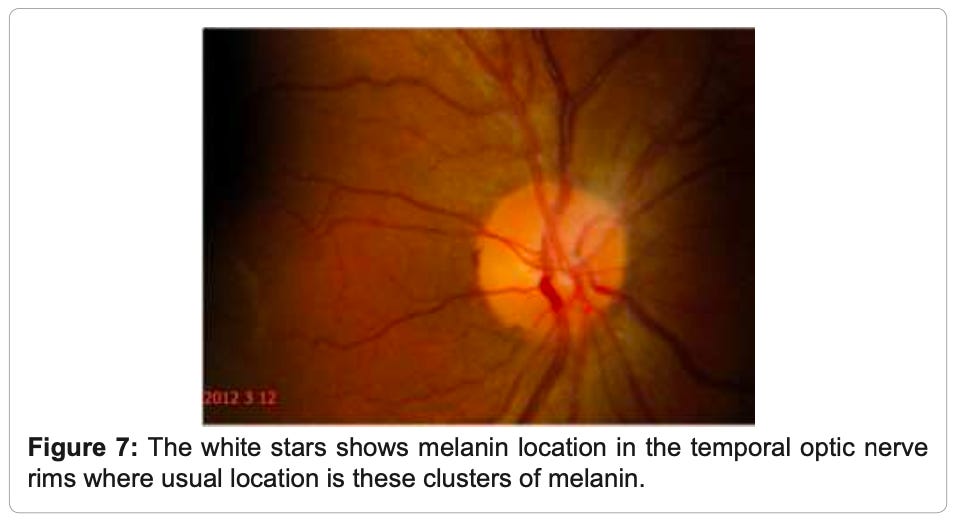

Around the same time, another researcher on the other side of the world was independently pursuing the melanin-energy connection, in a far more empirical way. Dr. Arturo Solís Herrera, a Mexican ophthalmologist and biochemist, stumbled onto melanin's secret while studying diseases of the eye. In the 1990s, Solís-Herrera was investigating the causes of blindness like glaucoma and diabetic retinopathy. As part of eye exams, he often observed the optic nerve in live patients and noted something intriguing: melanin was everywhere around the optic nerve, in the retinal pigment epithelium and choroid, forming a dark ring around the nerve head. This in itself wasn't news – anatomists knew the back of the eye is pigmented. But what struck Solís-Herrera was a question: Why would nature put a dense ring of melanin 2.5 centimeters deep inside the head, effectively behind the light-sensitive retina? It's like finding solar panels buried in a cave – seemingly out of place.

The conventional answer is that ocular melanin absorbs stray light, improving visual acuity and protecting tissues from light damage. Yet the placement and abundance of this pigment made Solís-Herrera wonder if something else was afoot. He began to hypothesize that melanin in the eye might be there to capture whatever light penetrates the tissues and use it to power local cells.

To test this, Solís-Herrera embarked on what became a 12-year odyssey of research, involving thousands of patient samples and countless experiments. In 2011, he and his colleagues announced a discovery that sounded almost heretical: melanin granules can dissociate water molecules, using light energy to split H₂O into hydrogen and oxygen. This is essentially the first step of photosynthesis – the same fundamental chemical feat performed by chlorophyll in green plants. Chlorophyll captures photons and uses that energy to crack water, releasing oxygen and storing energy in chemical form (hydrogen/electrons) which later generate sugars. Solís-Herrera was saying that melanin can do something analogous in our cells: act as a photoreceptor that breaks water into hydrogen (which carries energy) and oxygen. The hydrogen (likely in the form of molecular hydrogen or protons and electrons) could then be used by the cell's metabolic processes, just as plant cells use the outputs of water-splitting to eventually make ATP and sugars.

Skeptics scoffed – after all, if this were true, why hadn't biologists noticed it in the past 100 years? But Solís-Herrera's team had data. They demonstrated melanin's water-splitting in vitro and measured the currents and reaction products. In an article aptly titled "Beyond Mitochondria, What Would Be the Energy Source of the Cell?" (2015), they laid out their findings².

Initially, they too tried to fit this melanin-driven chemistry into known pathways of metabolism, scouring metabolic databases and pathways diagrams. But they found, as an aside, that even core pathways like the Krebs cycle are represented inconsistently in literature and databases – a sign that cellular metabolism is not fully understood. After years of trying to reconcile melanin's role with textbook biochemistry, they had an epiphany: perhaps melanin's photochemical energy isn't a minor supplement but a major contributor. They concluded that "the chemical energy released through the dissociation of the water molecule by melanin represents over 90% of cell energy requirements". In other words, they argue the vast majority of our ATP energy might actually come from light and water via melanin, while glucose (from food) is used mainly to build biomass (think of glucose more as "carbon bricks" than "fuel"). This flips the conventional view on its head. Glucose and mitochondria, in their scenario, are not the primary power sources but secondary – even "sacrosanct" roles that needed to be questioned.

By 2012, Solís-Herrera was already calling this concept "Human Photosynthesis." In a book chapter, he and his co-authors introduced melanin as "the animal analogue to chlorophyll", capable of harvesting electromagnetic radiation to dissociate water and release energy³. The term "human photosynthesis" is provocative, but it captures the essence of the hypothesis: that human cells have a light-driven energy pathway hitherto unknown. This new pathway doesn't produce sugars as plants do; instead, it directly produces ATP and other energy intermediates by coupling melanin's water-splitting to the cellular metabolic network.

The idea remained largely on the fringes for a few years, shared in alternative journals and conferences. It challenged deeply entrenched knowledge. Understandably, most biologists met it with skepticism or indifference – extraordinary claims, after all, require extraordinary evidence. Yet, as the 2010s progressed, more evidence began to trickle in, not just from Solís-Herrera's lab but from independent studies worldwide. Gradually, the narrative started to shift from pure hypothesis to something more tangible. It's a case study in how science advances: a wild idea arises, is initially ignored or criticized, but then data accumulates, experiments are reproduced, and slowly a conceptual framework starts to change. Indeed, as one biology textbook reminds us, new discoveries and technologies can "change the conceptual framework accepted by the majority of biologists". We may now be on the cusp of such a change regarding melanin. The next section examines the key discoveries that have moved melanin's role from vision to validation.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario