Sayer Ji

Oct 01, 2025

Read, share and comment on the X post dedicated to this article: https://x.com/sayerjigmi/status/1973392833919754517

Story at a Glance

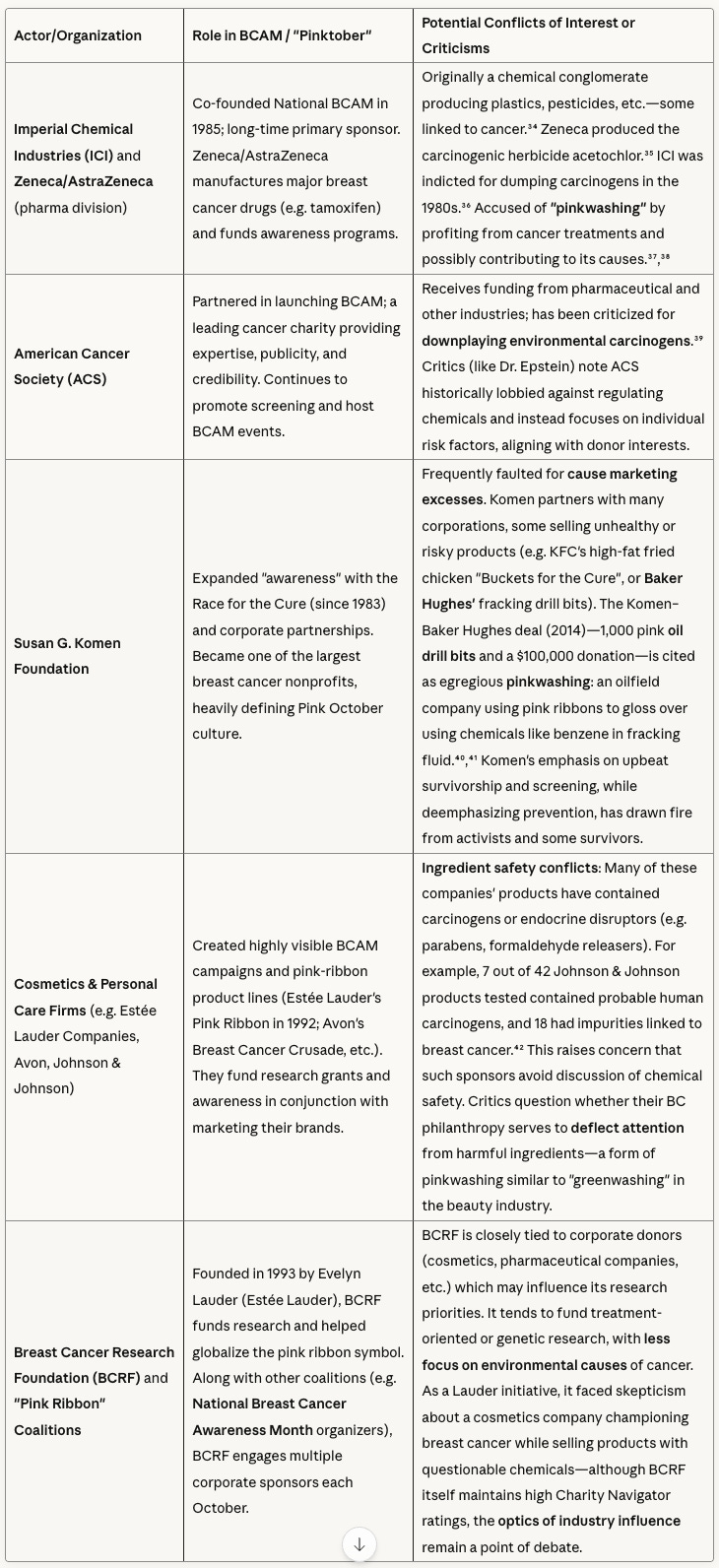

Corporate Origins: Breast Cancer Awareness Month was co-founded in 1985 by Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI)—a major chemical conglomerate whose portfolio included carcinogenic products—alongside health nonprofits, primarily to promote mammography screening and expand markets for cancer drugs.

Pinkwashing Documented: ICI/Zeneca and subsequent corporate sponsors engaged in systematic “pinkwashing”—profiting from breast cancer treatments while manufacturing chemicals linked to cancer causation, and using pink ribbon campaigns to deflect criticism from environmental and health controversies.

Agenda Control: Corporate funding steered BCAM messaging toward early detection (resulting in millions of overdiagnoses and overtreatments) and individual lifestyle changes while systematically avoiding discussion of industrial pollution, chemical exposures, and environmental carcinogens that contribute to rising breast cancer rates.

Conflicts Persist: Major breast cancer charities developed financial dependencies on sponsors selling products containing carcinogens or engaging in harmful practices, compromising their ability to advocate for comprehensive prevention strategies and regulatory reforms.

Introduction

Every October, “Pinktober” ushers in a flood of pink ribbons and breast cancer campaigns. Breast Cancer Awareness Month (BCAM)—established in 1985—has grown into a massive cause-marketing phenomenon. This report investigates BCAM’s origins and development, with a focus on the role of Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) and its pharmaceutical spinoff Zeneca (now part of AstraZeneca). It examines how these entities and others may have shaped BCAM to advance corporate agendas, through tactics critics dub pinkwashing (the breast-cancer analog of greenwashing).¹ We also analyze other key organizations (nonprofits, PR firms, industry groups) involved in BCAM’s creation and expansion, assessing potential conflicts of interest, instances of “pinkwashing,” and whether BCAM’s corporate sponsors have deflected attention from environmental or health controversies.

BCAM’s Origin: Industry and Nonprofit Collaboration (1980s)

Founding in 1985: BCAM was launched in October 1985 as a collaborative initiative between major health nonprofits and a pharmaceutical company’s foundation. According to the American Psychological Association, it began “as a collaborative effort between the American Academy of Family Physicians, AstraZeneca’s Healthcare Foundation, CancerCare, Inc., and a variety of other sponsors.”² Notably, AstraZeneca did not yet exist by name—it was then the pharmaceutical division of Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI), a British chemicals conglomerate. In effect, the American Cancer Society (ACS) partnered with ICI’s pharma arm (later spun off as Zeneca and eventually merged into AstraZeneca) to create National Breast Cancer Awareness Month.³ The campaign’s initial goal was explicitly to promote mammography as the most effective weapon against breast cancer, without mention of the profound health risks associated with the screening of asymptomatic populations.⁴ From the outset, BCAM was more about encouraging detection and screening than exploring why breast cancer was on the rise. Consult the GreenMedInfo mammography database for more information on their underreported, yet well-documented risks and harms.

Corporate Motivation: The decision of ICI/Zeneca to co-found BCAM was not purely altruistic. Internal analysis later revealed a practical business rationale: Zeneca had implemented an in-house breast cancer screening program for its employees in 1989, and by 1996 it found this early-detection program saved the company money in the long run. An estimated $400,000 was spent on the screening initiative versus a projected $1.5 million in costs had cancers gone undetected until later stages.⁵ In other words, catching cancer early among employees was cost-effective. As communications scholar Phaedra Pezzullo noted, “(Astra)Zeneca’s initial justification for NBCAM was one of basic accounting,” not a revolutionary vision for women’s health—it simply made financial sense to invest in early detection rather than pay for expensive late-stage treatments.⁶

Critics have long argued that Breast Cancer Awareness Month “was conceived and paid for by a British chemical company that both profits from this epidemic and may be contributing to its cause.”⁷ At the heart of this claim is Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI), whose pharmaceutical division, Zeneca, stood to gain from increased public awareness and widespread screening: more mammograms would likely lead to more breast cancer diagnoses, thereby expanding the market for Zeneca’s oncology drugs—most notably tamoxifen, a hormone therapy for estrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer. When Zeneca later merged with Astra AB in 1999 to form AstraZeneca, the new company also held the patent for Arimidex (anastrozole), another blockbuster drug used in breast cancer treatment. Meanwhile, ICI’s legacy as a major chemical manufacturer—associated with carcinogenic compounds such as paraquat, trichloroethylene, and chloroform—raised troubling questions about the company’s deeper motives for sponsoring BCAM. For many critics, this dual identity—profiteer of both potential causes and cures—embodies the very definition of “pinkwashing.”

Expansion of “Pinktober” Cause Marketing (1990s–2000s)

Rise of the Pink Ribbon: In the early 1990s, breast cancer awareness exploded into a broader movement, fueled by savvy marketing and new symbolism. In 1991, the Susan G. Komen Foundation (founded 1982) handed out pink ribbons to participants in its New York City “Race for the Cure,” and in 1992 Evelyn Lauder of the Estée Lauder cosmetics empire worked with magazine editor Alexandra Penney to create and popularize the pink ribbon as the ubiquitous emblem of the cause.⁸ Lauder also founded the Breast Cancer Research Foundation in 1993, blending corporate philanthropy with branding—Estée Lauder counters began distributing pink ribbons, cementing the link between cosmetics marketing and breast cancer awareness.⁹

“Pinktober” Marketing Blitz: By the late 1990s and 2000s, BCAM had morphed into a month-long marketing season often dubbed “Pinktober.” Major breast cancer charities (Komen, Breast Cancer Research Foundation, American Cancer Society, etc.) partnered with corporations to saturate October with cause-related promotions. Companies across industries rolled out pink products and donation campaigns. For example, Yoplait yogurt put pink lids on its cups, inviting customers to mail them in so the company would donate 10 cents per lid—a campaign critics noted relied on consumers (often unsuccessfully) completing burdensome steps for a tiny donation.¹⁰ Automotive giants like Ford sponsored breast cancer runs, even as vehicle exhaust emits carcinogens linked to breast cancer (such as 1,3-butadiene and PAHs).¹¹ Beauty and personal care companies from Avon to Johnson & Johnson became prominent sponsors; yet an analysis by the Environmental Working Group found dozens of J&J’s own cosmetic products contained ingredients classified as possible carcinogens or hormone disruptors¹²—a troubling irony noted by watchdogs.

By the 2010s, everyone was “in the pink.” NFL football players donned pink cleats and helmets each October, and corporations from Coca-Cola to General Mills plastered ribbons on products, pledging a portion of profits to breast cancer charities.¹³ This surge in participation undoubtedly raised money and public awareness on an unprecedented scale. However, it also amplified concerns that breast cancer philanthropy had become a “market-driven industry”, as scholar Samantha King observed,¹⁴ sometimes more attuned to corporate branding opportunities than to the actual needs of women’s health.

By the 2010s, everyone was ‘in the pink.’ NFL football players donned pink cleats and helmets each October, and corporations from Coca-Cola to General Mills plastered ribbons on products, pledging a portion of profits to breast cancer charities. This saturation was so complete that it began inviting satire. The Seinfeld skit ‘Ribbon Bully’ lampooned the social pressure of pink ribbon conformity—mocking the idea that not wearing or displaying a ribbon made one a target of moral policing. Such cultural critiques signaled that the pink ribbon had become not just a symbol of solidarity, but also a shorthand for performative awareness.

Perhaps the most egregious example of cause-marketing propaganda is the 2015 ‘Doing Our Bit for the Cure’ advertisement by Baker Hughes, which featured pink-painted fracking drill bits. As I reported previously, this campaign epitomized the cynical exploitation of breast cancer awareness - a company whose hydraulic fracturing operations potentially expose communities to carcinogenic chemicals was literally painting their drilling equipment pink and claiming to support cancer prevention.

ICI, Zeneca and AstraZeneca: Influence and Agenda

Corporate Lineage: Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) was a British chemical powerhouse with sprawling operations in plastics, pesticides, pharmaceuticals, and beyond.¹⁵,¹⁶ In 1993, ICI spun off its drug and agrochemical division into a new company, Zeneca, which later merged with Sweden’s Astra AB in 1999 to become AstraZeneca.¹⁷ The company behind Breast Cancer Awareness Month’s inception has always worn two hats: on one hand, a producer of widely prescribed breast cancer treatments—most notably Zeneca’s blockbuster drug tamoxifen (ironically, classified by the WHO as a ‘human carcinogen’) —and on the other, a manufacturer of known and suspected carcinogens used in agriculture and industry. These include paraquat (a highly toxic herbicide linked to oxidative damage and suspected cancer risk), trichloroethylene (a solvent classified as a human carcinogen), and chloroform, among others. This dual identity—profiting from both potential causes and treatments of cancer—lies at the heart of long-standing “pinkwashing” allegations.

Pollution and “Pinkwashing” Concerns: ICI’s history included environmental controversies that directly clash with its image as a breast cancer crusader. In the mid-1980s, around the time it helped launch BCAM, ICI was actually under U.S. EPA indictment for dumping carcinogenic chemicals into waterways.¹⁸ Observers have pointed out that sponsoring breast cancer awareness was a brilliant public relations maneuver for ICI and Zeneca to “spruce up [their] image” while under fire for environmental misconduct.¹⁹ In fact, Zeneca not only promoted BC awareness, it simultaneously manufactured fungicides and herbicides—including acetochlor, a chemical classified as a carcinogen.²⁰ A Zeneca chemical plant in Perry, Ohio was documented as the third-largest source of potential cancer-causing pollution in the entire United States.²¹ These facts alarm critics who see a blatant conflict of interest: the very company helping paint the world pink each October was profiting from—and possibly contributing to—the carcinogenic chemical exposures that might increase breast cancer incidence.

Health advocacy organizations have been outspoken about this conflict. Breast Cancer Action (BCA), a watchdog group, coined the term “pinkwashing” to describe companies that purport to care about breast cancer by promoting pink ribbon products, while engaging in practices that fuel the disease.²² AstraZeneca (Zeneca) is a classic example cited by BCA and others.²³,²⁴ As Breast Cancer Action Montreal put it, ”Major breast cancer awareness events turn a blind eye to primary prevention... because any discussion of the causes of breast cancer would necessarily focus on companies like AstraZeneca—major producers of potentially carcinogenic and harmful environmental toxins.”²⁵ Instead of highlighting environmental risks or chemical exposures, BCAM events (especially in early years) emphasized annual mammograms and individual lifestyle tips (diet, exercise, not smoking, etc.).²⁶,²⁷ Those personal health measures are important, but they do not address industrial causes—and conveniently, they do not threaten corporate sponsors’ interests. Critics argue this focus was strategic: it deflects attention from questions about toxic products and pollutants linked to breast cancer, many of which trace back to the very industries funding awareness campaigns.²⁸,²⁹

Control of the Narrative: By funding BCAM and related initiatives, Zeneca/AstraZeneca also positioned itself to influence breast cancer research priorities. Notably, Zeneca was a key player in clinical trials of chemoprevention—testing whether healthy but high-risk women could take tamoxifen to prevent breast cancer. Dr. Samuel Epstein, a prominent professor of environmental medicine, blasted Zeneca’s dominance in this arena.

He pointed out the troubling synergy in which a “spin-off of one of the world’s biggest manufacturers of carcinogenic chemicals” had gained significant control over breast cancer treatment and prevention efforts.³⁰ “This is a conflict of interest unparalleled in the history of American medicine,” Epstein said.³¹ He and others note that a company benefiting from cancer (by selling both causes and cures for it) has little incentive to promote prevention that might cut into its profits.³² Indeed, throughout the 1990s and 2000s, BCAM’s primary message remained “early detection” rather than “cancer prevention” via environmental and regulatory change. The American Cancer Society, BCAM’s early partner, likewise has been criticized for minimizing links between cancer and industrial chemicals—while receiving substantial donations from pharmaceutical, chemical, and mammography-related businesses.³³

In sum, evidence suggests that ICI/Zeneca helped shape BCAM’s agenda in ways that aligned with its corporate interests. The campaign steered public attention toward screening and optimism (”find the cure”), and away from contentious topics like pesticide regulation, pollutant bans, or corporate accountability for carcinogens. This alignment benefitted Zeneca/AstraZeneca’s bottom line—promoting the sale of screening technologies and cancer medications—while providing a halo effect for a company needing to rehabilitate its image.

The Unspoken Dangers of X-Ray Mammography

One of the most glaring omissions from Breast Cancer Awareness Month (BCAM) messaging is the risk posed by the very screening technology it so aggressively promotes: x-ray mammography. While presented as a life-saving intervention, mammography carries significant dangers that women are rarely told about.

Radiation Risks

The same ionizing radiation used in mammography is itself a well-established mammary carcinogen. Research published in the British Journal of Radiobiology found that the low-energy x-rays used in breast screening are four to six times more carcinogenic than previously assumedX-Ray Mammograms Starting at 40…. In other words, the “benefit-to-risk” models used to justify routine screening have consistently underestimated radiation-induced cancer risk by as much as 600%.

Cancer Promotion, Not Prevention

Beyond causing mutations, studies show that x-ray exposure can actually reprogram breast tissue, converting benign or low-risk tumor cells into malignant stem cells capable of spreading. What is sold as “prevention” may in fact be planting the seeds of future cancer. Go deeper into this topic here.

Overdiagnosis and Overtreatment

Radiation risk is compounded by the epidemic of overdiagnosis. Screening often detects non-life-threatening anomalies such as ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), leading to unnecessary mastectomies, chemotherapy, radiation, and lifelong drug use. According to Cochrane reviews, for every 2,000 women screened over 10 years, 1 life may be saved—but 10 women will undergo unnecessary treatment, and 200 will suffer trauma from false positives.

Ignoring Informed Consent

Despite these risks, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recently lowered the recommended age for mammograms from 50 to 40, exposing millions more women to radiation without fully disclosing the dangers. This violates the principle of informed consent: women are pressured to comply with screenings without being given the full truth about the potential harms.

Safer Alternatives

Radiation-free options such as thermography and advanced ultrasound exist, offering non-invasive, non-carcinogenic ways to monitor breast health. These technologies can detect physiological changes years before mammograms, without exposing women to harmful x-rays.

Major Players and Their Roles in BCAM’s Growth

Beyond ICI/Zeneca, numerous organizations have contributed to making BCAM and the pink ribbon into global phenomena. Their roles—and potential conflicts—are summarized below:

(Table Note: These are representative examples of key actors. Many other entities—from government agencies (e.g. CDC’s involvement in BCAM coalitions) to PR firms that orchestrate cause marketing—have played a part. The organizations above illustrate how mission-driven nonprofits and profit-driven companies intersect in BCAM, sometimes producing conflicts of interest.)

Cause Marketing vs. Corporate Agenda: Evaluating the Evidence

Thirty-plus years on, Breast Cancer Awareness Month has undeniably increased public awareness of a once-stigmatized disease, encouraging women to seek screening and raising billions for research. Mammography rates rose substantially in the 1980s–90s, and more breast cancers are caught at earlier stages today, yet survival rates remain the same, indicative of potentially immense levels of overdiagnosis - the 800lb gorilla in the room, when it comes to assessing whether or not mass mammography screenings have had a net benefit to women or not. BCAM and related campaigns have also fostered supportive communities for survivors and patients. These outcomes are often highlighted by campaign organizers as justification for the corporate partnerships.

However, the criticisms are equally significant. Increasingly, experts are recognizing that many early-stage conditions labeled as “cancer”—such as ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)—are often treated unnecessarily. These diagnoses may not pose a life-threatening risk, yet patients frequently undergo aggressive interventions. As a result, they can experience iatrogenic harm due to overdiagnosis and overtreatment. In some cases, both their quality of life and overall lifespan may be adversely affected.

To explore this issue in depth, see my exposé: The Cancer Deception: How Modern Medicine’s Fundamental Misunderstanding of Cancer’s True Causes Created a $43 Billion Overdiagnosis Industry.

Second, a growing body of investigative journalism and scholarly analysis indicates that some BCAM sponsors have leveraged the movement to advance a corporate-friendly agenda:

Selective Messaging: The educational content of BCAM often omits discussion of why breast cancer rates have climbed from about 1 in 20 women in the 1960s to about 1 in 8 today.⁴³ Environmental health scientists point to factors like chemical exposures (pesticides, plastics, industrial pollutants) as likely contributors. Yet BCAM’s founders and main sponsors historically avoided this topic. Instead, they emphasize behavior change by women (diet, exercise) or urge annual screening.⁴⁴ This focus conveniently steers around any blame on manufacturers of carcinogens. As the Sierra Club’s analysis tartly noted, “the horrible secret of the war against cancer is that preventing the causes of cancer will cut into the profits of those who fund the cure.”⁴⁵ Put plainly, companies funding BCAM have a vested interest in prioritizing detection/treatment (their profit centers) over prevention.

Most noteworthy is that if you search the website of ostensibly authoritative organizations like the National Breast Cancer Foundation and search their site for terms “carcinogen” you will get a null result. That’s astounding evidence that the very notion of their being a cancer-causing element to breast cancer in the environment, or related to exposures, has been removed from their website, and the minds of those who follow them. The same is true for terms like “overdiagnosis.”

“Pinkwashing” Exploits: The explosion of pink products and promotions each October has led to many cases where the cause marketing appears to benefit the company more than the cause. For instance, some product campaigns donate only a negligible percentage of sales to charity—or nothing at all, as a 2015 New York Times investigation found in certain “pink ribbon” sports merchandise.⁴⁶ Breast Cancer Action famously exposed how several cosmetics and household cleaning brands advertised with pink ribbons while containing toxins linked to cancer.⁴⁷,⁴⁸ They launched the “Think Before You Pink” campaign in 2002 to press for accountability. The term pinkwashing entered popular usage to describe cynical marketing ploys: Baker Hughes’ pink fracking drill bits became a case study in 2014, provoking public outrage and media ridicule.⁴⁹,⁵⁰ As The Guardian observed, ”A company whose product may contribute to increasing cancer rates is paying $100,000 to a cancer charity for the right to donate luridly-painted drill bits... Wow.”⁵¹ The stunt was widely seen as an attempt to “burnish their image” and deflect criticism of fracking’s health risks.⁵²,⁵³

Deflecting Controversy: In several documented instances, companies have timed breast cancer campaigns to offset negative attention. The Guardian notes that our instinct is to suspect “there’s something in it for them above and beyond the simple pleasure of doing good” when a firm makes an especially showy charity display.⁵⁴ This skepticism is often warranted: cause marketing can act as a shield. In ICI/Zeneca’s case, aligning itself with the sympathetic fight against breast cancer provided a reputational buffer while the company grappled with lawsuits and regulatory actions over chemicals. Similarly, cosmetics firms facing consumer questions about toxic ingredients often tout their breast cancer philanthropy as evidence of their commitment to women’s health—effectively changing the subject. This practice parallels greenwashing (where a polluter advertises eco-friendly efforts to obscure its environmental harm).⁵⁵ With pinkwashing, the feel-good glow of charity is used to neutralize critics and keep consumers onside.

Integrity of Nonprofits: The influx of corporate money has, some argue, made major breast cancer charities more cautious in challenging industry. Organizations like Komen and even ACS rely on sponsorships and partnerships that could be jeopardized by hard stances on issues like chemical regulation, industrial pollution, or even screening controversies (such as overdiagnosis from mammography). For example, Komen for years partnered with pharmaceutical companies that produce hormone replacement therapy drugs—yet was slow to educate women about the increased breast cancer risk of those very drugs.⁵⁶,⁵⁷ Advocates like Breast Cancer Action have filled the gap by pushing for a broader conversation on prevention and environmental links, effectively creating a “counterpublic” to the mainstream pink ribbon message.⁵⁸,⁵⁹ The tension between grassroots activists and the corporate-charity establishment suggests that BCAM’s narrative and priorities were indeed influenced by those underwriting it.

Conclusion

Breast Cancer Awareness Month began as an alliance between an industry giant and health charities, and it has always walked a line between altruism and corporate interest. On one hand, the campaign has achieved widespread awareness and raised funding for research, contributing to earlier detection and improved outcomes for many women. On the other hand, the historical record and investigative research make clear that Imperial Chemical Industries and Zeneca (AstraZeneca) helped shape BCAM in ways that also served their own agenda—promoting cancer screening (and drug sales) while skirting discussion of cancer prevention related to industrial chemicals. There is strong evidence of “pinkwashing”: companies have used BCAM’s positive image to gloss over environmental or health controversies, from chemical pollution to unhealthy products, and to present themselves as part of the solution even while being part of the problem.⁶⁰,⁶¹ Major nonprofits involved in BCAM’s growth, such as the ACS and Komen, have been critiqued for aligning with corporate sponsors to the point of compromising a full public health perspective.

In assessing BCAM’s legacy, it’s important to acknowledge both its public health successes and the corporate conflicts of interest entwined with its history. Breast cancer advocates now call for an approach that goes beyond symbolic pink ribbons—one that addresses environmental carcinogens, holds companies accountable, and prioritizes preventing cancer as much as curing it. The story of Breast Cancer Awareness Month, from its ICI-Zeneca origins to the Pinktober commercialization, is a cautionary tale of how noble causes can be co-opted by marketing and PR. Continued vigilance by independent researchers, activists, and ethical organizations will be needed to ensure that the fight against breast cancer is guided by women’s health interests first, rather than corporate image management.

What You Can Do Right Now: Use Food as Protection and Medicine

In a sea of pink-washed products and marketing, the real power of prevention may already be in your kitchen. As you’ve seen, nature offers a vibrant palette of pink and red foods—like red cabbage, pomegranates, beets, red apples, radishes, and purple sweet potatoes—that don’t just look beautiful, but are packed with compounds that support breast health on a cellular level.

You don’t need a prescription to start. Here’s what you can do today:

Add one cruciferous veggie to your meals this week: Red cabbage is rich in indole-3-carbinol (I3C), which supports estrogen metabolism and helps eliminate abnormal cells.

Snack on pomegranate seeds or drink pure juice: These powerful fruits act like natural aromatase inhibitors—reducing estrogen-driven cancer risk.

Roast beets or toss radish into your salads: These root vegetables offer potent antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and even tumor-suppressing properties.

Eat the apple peel: Red apples contain quercetin and anthocyanins, both shown to inhibit breast cancer growth in lab studies.

Try purple carrots or sweet potatoes: Their rich pigment indicates powerful antioxidant activity that helps combat DNA damage and oxidative stress.

Each of these choices represents a shift—from awareness to action, from passive support to proactive prevention. They’re not silver bullets, but they’re part of a powerful, holistic approach that also includes movement, stress reduction, and regular checkups.

The takeaway? Skip the pink packaging and start stacking your plate with the real thing. Your next meal could be part of your medicine cabinet.

For more information on natural, integrative, and root-cause oriented solutions for breast cancer prevention and treatment, consult our database on the subject, which contains over 3,800 peer-reviewed articles on the subject, and covers a wide range of problematic and therapeutic actions.

If you want to dive deep into the subject, supporting Substack subscribers (or GreenMedInfo members) can access my full Epoch Times presentation on the topic below:

Eat Your Way Out of Cancer w. Sayer Ji —(Members Only Viewing)

In this Epoch Times webinar, I share decades of research, personal healing experience, and practical wisdom on how to use food, mindset, and ancestral knowledge to prevent and even reverse the course of chronic disease—including cancer.

Finally, for those who want to dive even deeper into the topic, my book REGENERATE: Unlocking Your Body’s Resilience with the New Biology focuses on the true origins of cancer, which is a prerequisite for finding effective approaches to preventing and treating it. You can obtain a copy here.

You can also enroll in my upcoming week-long free masterclass on the topic, Regenerate Yourself, beginning on Oct. 13th, or get the entire multi-year educational program immediately here.

References

McGee, Suzanne. “How Breast Cancer Research Benefits from Fracking (and Other Abominations).” The Guardian, October 16, 2014. https://www.theguardian.com/money/us-money-blog/2014/oct/16/baker-hughes-pinkwashing-corporate-hypocrisy.

American Psychological Association, Women’s Programs Office. “October is National Breast Cancer Awareness Month.” 2010. Archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20101212140607/http://apa.org/pi/women/resources/newsletter/2010/10/breast-cancer.aspx.

“Breast Cancer Awareness Month.” Wikipedia. Accessed 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Breast_Cancer_Awareness_Month.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Pezzullo, Phaedra C. “Resisting ‘National Breast Cancer Awareness Month’: The Rhetoric of Counterpublics and Their Cultural Performances.” Quarterly Journal of Speech 89, no. 4 (2003): 345–365.

“Breast Cancer Awareness Month.” Wikipedia.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Breast Cancer Action Québec. “Profits in Pink.” 2004. https://acsqc.ca/content/profits-pink.

Ibid.

Ibid.

LAist. “Do Corporate Sponsorships Derail the Message of Breast Cancer Awareness?” October 31, 2013. https://laist.com/shows/airtalk/do-corporate-sponsorships-derail-the-message-of-breast-cancer-awareness.

King, Samantha. Pink Ribbons, Inc.: Breast Cancer and the Politics of Philanthropy. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006. https://www.upress.umn.edu/9780816648993/pink-ribbons-inc/.

“Imperial Chemical Industries.” Wikipedia. Accessed 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Imperial_Chemical_Industries.

Ibid.

Ibid.

May, Elizabeth, and Samuel Epstein. “Cancer and the Environment.” Sierra Club Canada, 1999/2000. https://archive.sierraclub.ca/national/programs/health-environment/toxics/cancer-environment.shtml.

Ibid.

Breast Cancer Action Québec. “Profits in Pink.”

Ibid.

“Breast Cancer Awareness Month.” Wikipedia.

Breast Cancer Action Québec. “Profits in Pink.”

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

May and Epstein. “Cancer and the Environment.”

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Breast Cancer Action Québec. “Profits in Pink.”

Ibid.

May and Epstein. “Cancer and the Environment.”

“Breast Cancer Awareness Month.” Wikipedia.

Ibid.

May and Epstein. “Cancer and the Environment.”

McGee. “How Breast Cancer Research Benefits from Fracking.”

Ibid.

Breast Cancer Action Québec. “Profits in Pink.”

May and Epstein. “Cancer and the Environment.”

Breast Cancer Action Québec. “Profits in Pink.”

May and Epstein. “Cancer and the Environment.”

“Breast Cancer Awareness Month.” Wikipedia.

Breast Cancer Action Québec. “Profits in Pink.”

Ibid.

McGee. “How Breast Cancer Research Benefits from Fracking.”

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

May and Epstein. “Cancer and the Environment.”

Ibid.

“Breast Cancer Awareness Month.” Wikipedia.

Breast Cancer Action Québec. “Profits in Pink.”

May and Epstein. “Cancer and the Environment.”

McGee. “How Breast Cancer Research Benefits from Fracking.”

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario