Sayer Ji

Oct 01, 2025

[Note: Though my birth name is Douglas Sayer Ji, I formally changed it to Sayer Ji in 2018 after thirty years of exclusive use. Wikipedia’s insistence on privileging my former name not only disregards my identity, it also violates its own policies on biographies of living persons (WP:BLP) and the use of common names (WP:COMMONNAME)—an irony that sets the stage for what follows.]

I am grateful and honored to have this reposted on X by Larry Sanger—Wikipedia’s co-founder and a consistent voice for truth.” You can do the same here.

This document chronicles my personal experience of how Wikipedia’s article about me exemplifies systemic bias and the weaponization of the platform against individuals who challenge established narratives. My case reveals:

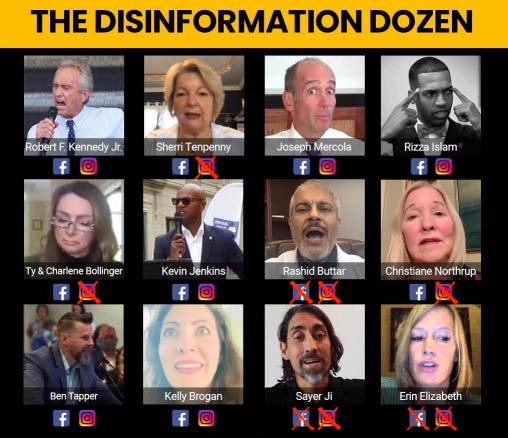

Coordinated Timing: My Wikipedia page was created May 20, 2021—just four days before the Center for Countering Digital Hate (CCDH) published its “Disinformation Dozen” report—with editors explicitly admitting the page was prompted by my inclusion in that report.

Policy Violations: The article violated Wikipedia’s own Biographies of Living Persons (BLP) policies through pejorative labeling, reliance on blacklisted sources (the CCDH report was flagged as spam by Wikipedia’s own filters), and editorial language that editors internally acknowledged was intended to “shame” rather than inform.

Amplification Loop: The defamatory content spread across the digital ecosystem through AI systems (ChatGPT, Perplexity.ai), search engines, and mainstream media, creating a self-reinforcing cycle where Wikipedia’s biased framing became accepted as fact across platforms.

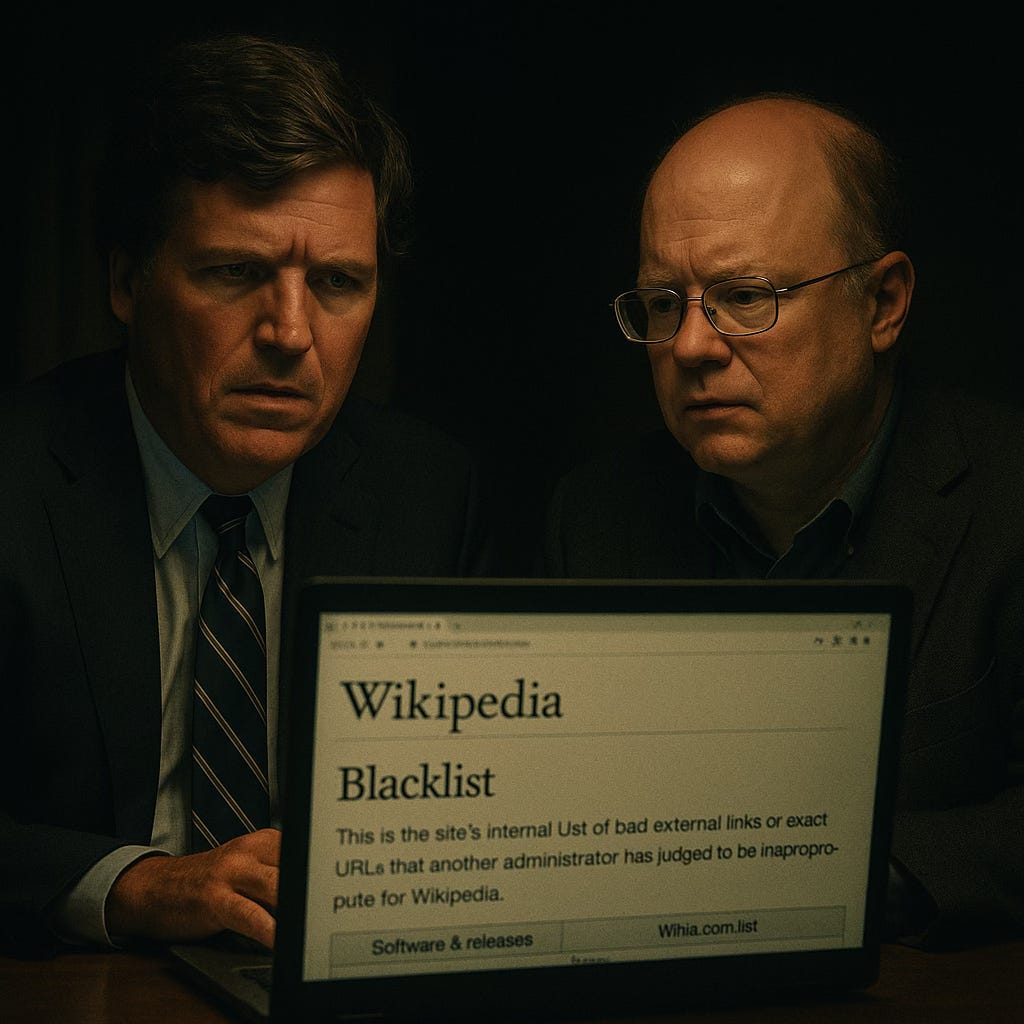

Systemic Credibility Crisis: The Sept. 2025 Tucker Carlson interview with Wikipedia co-founder Larry Sanger brought widespread public attention to Wikipedia’s ideological filtering, source blacklisting, and potential infiltration by intelligence agencies, marking what may be a turning point in the platform’s credibility.

They didn’t just come for my work. They came for my name. My identity. My ability to exist in the digital age without a scarlet letter permanently etched beside it.¹

On May 20, 2021, a Wikipedia article about me appeared out of nowhere—and it was anything but neutral. The entry went live just four days before the Center for Countering Digital Hate (CCDH) published its now-infamous “Disinformation Dozen” report, which named me among twelve people allegedly responsible for the majority of “anti-vaccine” content online.² The timing was no coincidence. The Wikipedia editor who created my page, an alias “Robincantin,” openly admitted on the article’s Talk page that the entry was prompted by my inclusion in the coming CCDH report: ”There are of course hundreds of news media articles naming him as one of the ‘Disinformation Dozen’. I chose to reference only the original research report and one news article.”³ In other words, my Wikipedia biography was created explicitly to showcase an accusation—not to chronicle my life or work, but to cement a narrative seeded by a political advocacy group

What followed is a case study in how Wikipedia can be weaponized against individuals—through deliberate violations of the site’s own rules, reliance on biased or blacklisted sources, and editorial “gatekeeping” in service of a defamation campaign. My experience, backed by Wikipedia’s own archives and editors’ words, exposes how the world’s largest encyclopedia has been co-opted to discredit independent voices. It also raises urgent questions about Wikipedia’s broader credibility crisis—an issue now drawing public scrutiny thanks to whistleblowers like co-founder Larry Sanger and high-profile discussions on platforms like Tucker Carlson’s show. This is my testimony of that ordeal, the systemic corruption it reveals, and why many see Wikipedia at a crossroads: teetering from a flawed reference tool into an instrument of information warfare.

A Biography Built to Shame—Violating Wikipedia’s Own Rules

From day one, my Wikipedia page flouted the site’s foundational policies on Biographies of Living Persons (BLP), which demand strict neutrality and high-quality sourcing for contentious claims. The article’s opening line labeled me ”the founder of alternative medicine portal GreenMedInfo, a website known for promoting various pseudoscientific publications.”⁴ This derogatory framing was presented as fact, without proper context or reliable sourcing. In reality, GreenMedInfo—the site I founded—is a database of over 100,000 study abstracts drawn largely from the National Library of Medicine’s PubMed journal index.⁴ Far from peddling homemade quackery, my platform curates peer-reviewed research on natural health. Branding it “pseudoscientific” not only ignores that scientific content, it twists the truth to prejudice readers from the outset. By dismissing my work as pseudoscience without engaging any of the actual evidence, Wikipedia’s editors revealed a clear bias against alternative medicine perspectives.⁴

Worse, the Wikipedia entry leaned on disputed and frankly disreputable sources to impugn me. Chief among them was the CCDH report itself—the very document that mis-tagged me as a top misinformation spreader. That report was so dubious that Wikipedia’s own spam filters had blacklisted its host domain. As one Wikipedia administrator later noted in reviewing the page, ”Not one but two PDFs hosted on ‘filesusr.com’ written by a political advocacy group... note that I literally can’t even link these URLs in [the deletion forum] despite being an admin because they are on the global spam blacklist.”⁵ In short, Wikipedia’s software recognized the CCDH report as junk, but determined editors found ways to circumvent the spam block in order to use it as a citation against me.⁵ They bent their own rules to include a source so questionable that the platform’s automated systems flagged it as spam.

Such actions blatantly violate Wikipedia’s BLP policy, which is unequivocal: contentious material about living people must be rigorously sourced and immediately removed if not.⁶ Yet my page stood as a monument to BLP violationsfrom the start. In fact, by 2024, even some within Wikipedia could not ignore how egregious the situation had become. In May 2025, an editor using the handle “Dakotacoda” attempted a good-faith cleanup of my article. Dakotacoda noted on the Talk page that ”this article contains multiple, egregious violations of core policy... editorial language, pejorative labeling, unsourced claims... all of which violate WP:BLP and WP:NPOV.”⁷ The editor systematically removed or reworded the most blatant policy breaches, aiming to bring the article in line with Wikipedia’s standards.

The response? Immediate reversion and reprisal. Other long-time editors swooped in to undo Dakotacoda’s corrections almost as fast as they were made, accusing the user of “whitewashing” my page.⁸ Every pejorative label and poorly sourced claim—the very elements that violated Wikipedia’s core principles—were promptly restored. Dakotacoda was even hit with a one-week suspension from editing Wikipedia.⁸ In Wikipedia’s Orwellian internal logic, it seems, trying to remove defamation from a biography equated to a punishable offense.

Perhaps the most damning evidence of Wikipedia’s bias comes from the words of its own editors, caught in moments of candor. In January 2024, a discussion took place among Wikipedia administrators and editors about whether to delete my page, given the lack of reliable sources and multiple policy violations it exhibited.⁹ One might think this would be an open-and-shut case for deletion or drastic cleanup—after all, Wikipedia is not supposed to be a place for unsourced defamation. But several veteran editors argued strenuously to keep the page, explicitly for the purpose of debunking or shaming me. “Ji is a major player in the antivax disinformation world, and having an article (properly-sourced and in line with WP:FRINGE) on him would help fill the vacuum where such disinformation thrives,” one editor wrote.¹⁰ Another admitted that even if I didn’t meet the usual notability criteria, the page should remain simply because I’m on the “Disinformation Dozen” list¹¹—essentially saying the CCDH’s accusatory list by itself justified a Wikipedia entry on me.

In other words, by some Wikipedians’ own admission, my page existed “not to inform, but to counter [my] influence.” It was not a neutral biography; it was a digital pillory.¹² As if to drive that point home, a seasoned Wikipedia administrator chimed in during the same discussion and described my article as a textbook “WP:COATRACK”—that is, an article created primarily to advance a certain point of view, rather than to neutrally cover its subject.¹³ “This isn’t significant coverage and the guy is not notable,” the admin observed, acknowledging that under normal circumstances a flimsy page like this would be discarded.¹⁴ Yet the page persisted. Why? Because, the admin noted with a dose of quiet outrage, *”the consensus has changed in that articles that shame a living person who is otherwise notable can remain... this is a change from the usual outcome in 2007–2009.”*¹⁵

Let that sink in: Wikipedia’s own insiders essentially acknowledged that the site’s standards have shifted to allow “shaming” articles. What would once have been swiftly deleted as a BLP nightmare was now kept alive as a cautionary tale—a means to “shame a living person” for perceived transgressions.¹⁵ The “free encyclopedia” had embraced a role as judge, jury, and reputational executioner.

Bias, Blacklists, and Bad Sources: The Corruption of Wikipedia’s Content

Zooming out from my personal ordeal, a troubling picture emerges of systemic bias in Wikipedia’s sourcing and editorial processes. My page is a particularly stark example, but many of its elements reflect broader patterns in Wikipedia today.

One issue is the double standard in sources. Wikipedia maintains an official policy on so-called “deprecated” sources—outlets deemed so unreliable that they are generally forbidden as references. In a recent interview, Larry Sanger rattled off some examples: “The blacklisted sources are Breitbart, Daily Caller, Epoch Times, Fox News, New York Post, The Federalist, so you can’t use those as sources on Wikipedia,” he told Tucker Carlson.¹⁶ Indeed, Wikipedia’s own “Reliable sources/Perennial sources” list codes many conservative or non-mainstream media in red (deprecated or blacklisted) while mainstream liberal-leaning outlets are green-lit as “reliable.”¹⁷,¹⁸ Breitbart News, for instance, is formally blacklisted—any attempt to cite it is automatically blocked by the site.¹⁹ The Epoch Times and Daily Caller (the latter co-founded by Carlson) are marked “deprecated” and “generally unreliable” in Wikipedia parlance.¹⁹ Even the New York Post, America’s oldest continuously published daily, is flagged as “questionable” and usable only in limited circumstances.¹⁹ On the flip side, establishment outlets like The New York Times, CNN, The Washington Post, as well as advocacy organizations like GLAAD or the ADL, are treated as inherently reliable sources by Wikipedia’s criteria.²⁰

The intent of such source deprecation policies—to maintain quality control—might be reasonable in theory. But in practice, it has contributed to an ideological filtering of Wikipedia content. By banning or discouraging numerous outlets on one end of the political spectrum, Wikipedia tilts the pool of allowable information. When it comes to topics like alternative medicine, vaccines, or disfavored political views, evidence and perspectives from those banned outlets are essentially cordoned off from Wikipedia’s pages. This creates a knowledge vacuum that can be filled by one-sided reports from “approved” sources.

My page exemplifies this. It leans heavily on a blog post by Jonathan Jarry of McGill University’s Office for Science and Society—a piece that accuses me of “cherry-picking” studies to support natural cures. Notably, Jarry’s blog is not a peer-reviewed source; it’s an opinionated piece from an organization with a very particular mission (debunking “alternative” health claims). Under Wikipedia rules, such self-published commentary is generally frowned upon for biographies—yet my page cites it liberally. Meanwhile, there is no mention on Wikipedia that McGill’s Office for Science and Society, and McGill University itself, have received significant funding from pharmaceutical companies like Merck and Pfizer.²¹ This conflict of interest—the fact that a pharma-funded institution is critiquing a prominent natural health advocate—is completely glossed over on Wikipedia. Jarry’s blog is presented as if it were objective scientific gospel, rather than what it is: a partisan take from a party with skin in the game.²²

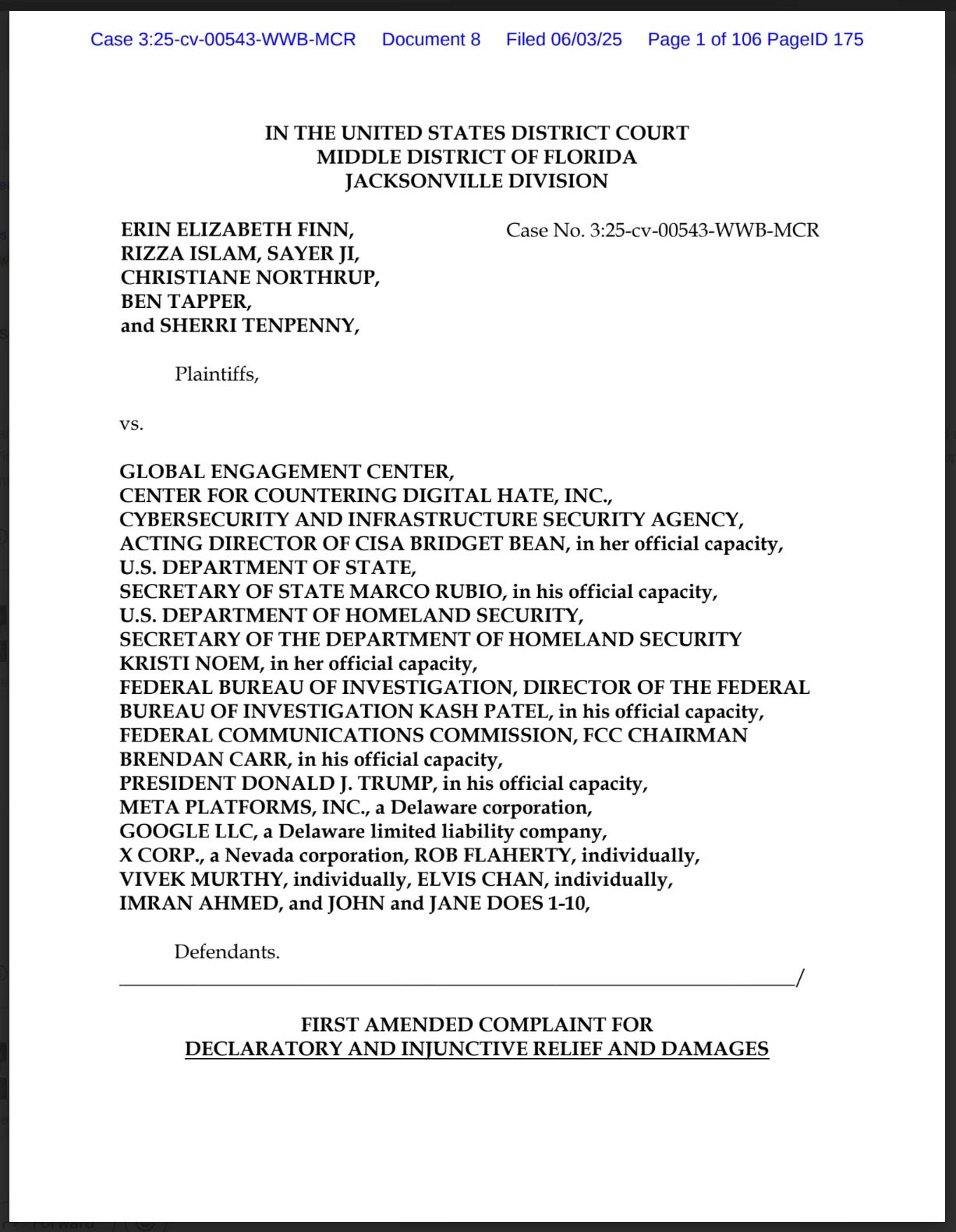

In contrast, evidence favorable to me or critical of my accusers is hard to find on Wikipedia. For example, Meta (Facebook’s parent company) publicly refuted the CCDH’s “Disinformation Dozen” claims shortly after they spread. Meta’s Vice President of Content Policy wrote in August 2021 that “there isn’t any evidence to support” the statistic that 12 people were behind 73% of online vaccine misinformation, revealing that in reality those individuals accounted for ”only about 0.05% of all views of vaccine-related content.”²³ This was a staggering 1,300-fold error in the CCDH’s core claim. Meta even branded the CCDH report “faulty” and “without evidence.”²³ Yet my Wikipedia page never prominently notes this vindicating fact—it simply repeats that I was “identified” as a top misinformation spreader, without clarifying that the identifier was a discredited activist report.²⁴ The House Judiciary Committee under Rep. Jim Jordan later issued subpoenas to investigate the coordination behind the “Disinformation Dozen” narrative, and a civil lawsuit (Finn v. Global Engagement Center) was filed in federal court challenging the very claims made about these individuals.²⁵ But again, none of that context made it into Wikipedia’s portrayal of me. The narrative was set: I’m a “misinformation disseminator,” and inconvenient details that undermine that narrative are ignored.

All of this paints a picture of Wikipedia’s systematic corruption on sensitive topics. Anonymous editors and powerful administrators serve as gatekeepers, deciding which sources and viewpoints are acceptable. If those gatekeepers share a particular bias (be it pro-pharmaceutical, pro-establishment, or otherwise), the content will inevitably reflect it. And because these actors operate in the shadows of pseudonyms, they aren’t easily held accountable. As I’ve lamented, ”If someone publishes lies about you in a newspaper, you can sue the newspaper. But when Wikipedia publishes defamatory content, whom do you sue?”²⁶ The Wikimedia Foundation disclaims responsibility (citing Section 230 immunity for user-generated content), the editors hide behind usernames, and the originators of the false claims might be overseas groups or even undisclosed government contractors.²⁶ “The editors use pseudonyms. The sources are advocacy groups based overseas. Or sock puppet accounts within intelligence agencies, foreign and domestic,” I’ve observed.²⁷ It’s a Kafkaesque scenario: a defamatory claim on Wikipedia can echo around the world, yet there is no clear person to hold accountable for it.

Larry Sanger’s recent comments add a chilling layer to this. The Wikipedia co-founder suggests that what we are witnessing is not just ideological bias, but the possible infiltration of Wikipedia by intelligence agencies and political operatives.²⁸,²⁹ Sanger points to research showing heavy editing traffic from CIA and FBI IP addresses, and notes that certain powerful figures in Wikipedia’s orbit have openly aligned with government censorship efforts.²⁸,³⁰ Notably, Sanger highlighted recent statements by Katherine Maher, former CEO of the Wikimedia Foundation, who has collaborated with governments to police online speech and dismissed the notion of objective truth in favor of relativism.³⁰ To Sanger—who left Wikipedia long ago over disagreements about its direction—these revelations “align with the increasing bias and systematic silencing” he has observed on the platform.³¹ In his blunt assessment, Wikipedia has become “an arrogant and controlling oligarchy” ruled by “a shadowy group of anonymous amateurs and paid shills”, which has ”centralized epistemic authority in the hands of an anonymous mob.”³²,³³ The scary part, Sanger adds, is that unlike a social media company with a CEO, “there isn’t anyone who is responsible for Wikipedia’s content”—the system is leaderless by design, which makes its capture by unseen forces all the more insidious.³⁴

For me, all of this rings painfully true. My personal experience suggests that powerful interests—a transatlantic network of NGOs, media, perhaps even state actors—had both motive and opportunity to weaponize my Wikipedia profile. The CCDH, which kicked off the “Disinformation Dozen” campaign, is a UK-based organization with opaque funding that has worked closely with officials in the U.S. (the Biden administration cited their work in pressuring social media companies). It’s exactly the kind of group one might suspect of coordinating with others to suppress “dissident” voices. As I’ve put it, Wikipedia has become a “digital proxy” for a new form of warfare against dissent³⁵—a proxy that allows reputations to be destroyed by remote control, without the dirty work ever being traced back to government censors or corporate PR firms. “This isn’t conspiracy theory. It’s conspiracy fact, documented in their own words,” I’ve written, pointing to the trove of on-wiki evidence I gathered.³⁶ Indeed, the talk-page admissions, the blacklisted links, the overt declarations of a shaming agenda—they are all preserved in Wikipedia’s records, if one knows where to look.³⁷

The Feedback Loop: How AI, Google and Media Amplify Wikipedia’s Narrative

Wikipedia’s outsized influence means that what starts on a niche Talk page or in an obscure edit war can quickly echo across the entire digital information ecosystem. My saga illustrates this phenomenon in stark detail. The defamation on my Wikipedia page did not stay confined to Wikipedia—it spread to search engines, AI assistants, and even mainstream news outlets, creating a reinforcing loop that is difficult to break.

By 2023, AI-driven tools and platforms had begun scraping Wikipedia’s content to generate their own answers and summaries. I noticed that when people queried certain AI chatbots or search assistants about me, the responses mirrored Wikipedia’s biased framing. For instance, the AI search engine Perplexity.ai described me in virtually the same terms as the Wikipedia intro—calling me an “alternative medicine” figure who promotes “pseudoscientific claims” and highlighting the CCDH’s misinformation charge.³⁸,³⁹ In effect, these AI systems regurgitate Wikipedia’s defamatory content as if it were established fact, because Wikipedia is treated as a highly authoritative source in their models.⁴⁰ I’ve written that by 2023, **ChatGPT and Perplexity were “scraping Wikipedia to generate summaries about me, spreading these violations across the entire digital ecosystem.”**⁴¹ Ask an AI “Who is Sayer Ji?” and you get the Wikipedia version of me—context stripped, counter-evidence omitted, and caveats lost.

Academic researchers have a name for this: the “vicious cycle” of misinformation reinforcement.⁴² A biased Wikipedia article feeds a biased AI summary, which in turn influences public perception and even media coverage, which then gets cited back on Wikipedia as further validation. It’s a self-perpetuating feedback loop. As an MIT study noted (and I’ve cited), once false or slanted information is seeded, each layer of reproduction—AI, news, social media—adds a patina of legitimacy.⁴² Before long, the original falsehood is entrenched in the public consciousness, repeated so widely that few remember it came from a single dubious report. In my case, the CCDH’s flawed claim begot a Wikipedia article, which begot countless references in Google results (over 192,000 hits for “Disinformation Dozen” at one point, ”with not a single correction, qualification or retraction”⁴³), which begot AI answers and media labels, which all came back around to fortify the Wikipedia entry. Breaking out of this cycle is herculean—where would one even start, when the misinformation hydra has so many heads?

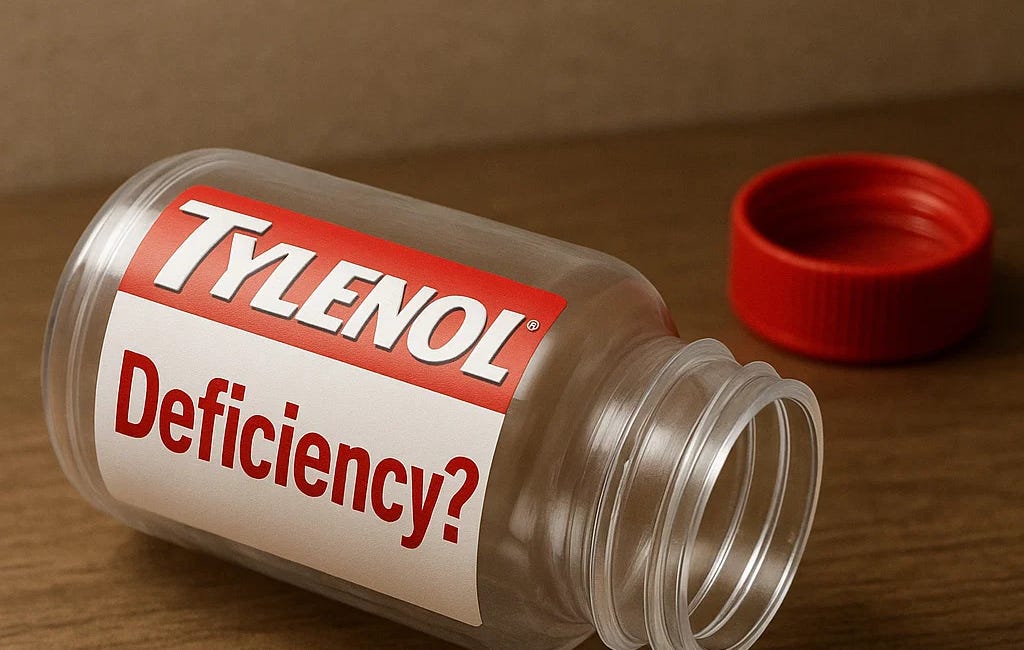

Traditional media, ironically, have now begun taking cues from Wikipedia and that same activist narrative. The Wall Street Journal’s September 26, 2025 article “Inside the Crisis at Tylenol” provides a perfect example. The article’s ostensible topic was lawsuits over Tylenol’s possible link to autism—something I’ve researched and written about extensively. But rather than engage with the scientific evidence I’ve curated (dozens of peer-reviewed studies suggesting prenatal acetaminophen exposure could be a factor in neurodevelopmental disorders), the WSJ piece chose to zero in on my reputation. It introduced me as “the vaccine skeptic” and “promoter of Covid-19 misinformation” whose Substack post had been shared by Robert F. Kennedy Jr.⁴⁴,⁴⁵ This was a classic guilt-by-association setup—painting me as an anti-vax disinformation peddler to preemptively undermine my credibility on any topic, including Tylenol safety.

I have objected to be characterized with the “anti-vaccine” label —I advocate for informed consent, choice, and safety, not blanket opposition⁴⁶—and the “Covid-19 misinformation” label is provably false and defamatory in light of the data. It traces straight back to the CCDH/Wikipedia narrative. I was anticipating that the WSJ might repeat this libel, so I warned the reporter in advance, providing all the counter-evidence: Meta’s takedown of the 73% myth, the fact that the “Disinformation Dozen” accounted for only 0.05% of Facebook’s content, even the detail that Congress found the CCDH claims dubious enough to investigate.⁴⁷,²⁵ Yet the WSJ went ahead and printed the “promoter of misinformation” line anyway.⁴⁸ This suggests that by 2025, the Wikipedia/CCDH narrative had fully penetrated legacy media fact-checking—or worse, that some journalists feel licensed to ignore primary facts in favor of a convenient defamatory tag.

WSJ Claims 'Tylenol Deficiency' Causes Autism — While Defaming My Work

Read, comment, and share the X post dedicated to this article: https://x.com/sayerjigmi/status/1971968064255086802

The upshot is that Wikipedia’s portrayal of me became a one-stop shop for detractors. Journalists on a deadline could grab a quick negative descriptor from Wikipedia; Google’s algorithm would surface the controversy high in search results; and AI assistants would dutifully echo the same talking points to countless users asking about me. The initial context—that the 73% figure was bogus, that my site is grounded in published research, that I’ve been targeted for challenging pharmaceutical dogmas—all of that gets lost in the noise. Instead, I’m presented to the world through a distorted funhouse mirror: anti-science crank, top misinformation “dozen,” cherry-picking grifter. The stigma manufactured on Wikipedia follows me everywhere in the digital realm.

Tucker Carlson and Larry Sanger Sound the Alarm

For years, Wikipedia’s critics struggled to get mainstream attention for these issues. That changed in late 2025, when a high-profile media personality and a Wikipedia insider joined forces to pull back the curtain. Tucker Carlson’s interview with Larry Sanger—aired on Carlson’s online show after his departure from Fox News—became a cultural flashpoint, bringing Wikipedia’s credibility crisis into the spotlight for a much broader audience.

During the interview, Sanger guided Carlson through Wikipedia’s “perennial sources” blacklist, essentially confirming what many had suspected: that Wikipedia had systematically purged or discredited many outlets that don’t align with a left-of-center, establishment view.¹⁶ As noted above, Sanger listed examples like Breitbart, The Daily Caller (Carlson’s own outlet), and even Fox News itself being red-flagged on Wikipedia.¹⁶ Carlson, seeing it in real time, was stunned. “Come on! ... This is kind of incredible. I never hear about this! And we don’t know who made this decision?” he exclaimed, as he scrolled through Wikipedia’s color-coded list.⁴⁹ Sanger pointed out the opacity of it all: the guidelines were written by an account called “Mr. X” and others—pseudonyms behind which ideological moderators operate without public scrutiny.⁵⁰

That segment quickly went viral on social media. “Why is no one talking about this?” Carlson asked during the show, baffled that a site as influential as Wikipedia could quietly ban major news sources and skew information without broader public knowledge.⁵¹ Sanger’s reply was telling: *”It’s simply embarrassing for the left, so the left aren’t going to report about it.”*⁵¹ In other words, mainstream media—which often rely on those very Wikipedia articles for their own research—had little incentive to expose Wikipedia’s tilt, since they largely benefit from being the “approved” sources while their competition is labeled fake news.

The reaction on X (Twitter) and beyond was immediate. Prominent figures in politics and media who had long harbored suspicions about Wikipedia now had validation from the site’s co-founder. Senator Ted Cruz tweeted the clip with the comment, “Wikipedia is brazen propaganda.” Tom Fitton, president of Judicial Watch, wrote that Wikipedia is ”a smear machine for the Left.”*⁵² Even Donald Trump Jr. weighed in, saying ”Wikipedia regularly defames conservatives with lies and smears, so this explains a lot.”*⁵³ The criticisms went far beyond me or any single case—they were calling out Wikipedia’s overall credibility and alleging a deep-seated political bias.

Meanwhile, Elon Musk—who has tangled with Wikipedia before—took the opportunity to propose an alternative. He quipped that he would fund a competitor called “Grokipedia” (a nod to his AI project Grok), promising it ”⁵⁴ Musk’s frustrations with Wikipedia (he once jokingly offered them $1 billion if they renamed themselves “Dickipedia”) are well known, but here he was channeling a broader sentiment: that Wikipedia had so lost the public’s trust, tech innovators might step in to reinvent the concept of a crowdsourced encyclopedia. In response, Larry Sanger cautiously welcomed the idea of alternatives, tweeting “Let’s hope it won’t be as biased as Grok itself”—a wry reminder that any new platform must learn from Wikipedia’s mistakes.⁵⁵

The Tucker–Sanger conversation crystallized a moment of public awareness. What had been brewing in niche circles—on Substacks, alternative health blogs, or in congressional committee letters—was suddenly water-cooler talk. Wikipedia’s “neutral point of view” facade had cracked, for all to see. When a primetime pundit with millions of viewers expresses shock that Wikipedia has systematically excluded half the media spectrum, people take note. When the co-founder of Wikipedia says the site can’t be trusted and hints that CIA and FBI agendas may be in play, it sets off alarm bells. This was the encyclopedia that for two decades many treated as gospel for quick facts—now its biases were headline news.

For me and others who’ve been on the receiving end of Wikipedia’s smear machine, the Carlson-Sanger interview was a form of vindication. It signaled that the broader public is finally waking up to what I call “Wikipedia’s editorial capture.” No longer was it a fringe position to question Wikipedia’s objectivity—it had become a topic for mainstream discourse and even late-night humor. The fallout also put Wikipedia’s management on the defensive, as critics pressed the Wikimedia Foundation for answers about how sources are chosen and how political influence is managed. (To date, Wikipedia’s leadership, including co-founder Jimmy Wales, generally dismiss these accusations; Wales insists the site still has a “very long tradition” of neutrality⁵⁶—despite mounting evidence to the contrary.)

Crossing the Rubicon: An Encyclopedia Turned Instrument of Information Warfare

All these developments point to a stark conclusion: Wikipedia has crossed a credibility Rubicon. What was once seen as a flawed but mostly good-faith repository of human knowledge has, in critical areas, morphed into something else entirely—an instrument for controlling narratives and delegitimizing individuals or ideas that challenge orthodoxies. In the process, Wikipedia risks forfeiting the trust that made it a global utility in the first place.

My story encapsulates this transformation. My Wikipedia page was not the product of organic, detached editors neutrally documenting a public figure’s life and work. It was born out of a coordinated campaign (timed with the CCDH report), filled with loaded language and dubious sources, and maintained through aggressive editorial tactics that flouted the site’s own guidelines. The goal of the page was not to inform, but to warn: to serve as a permanent digital indictment of me as a spreader of dangerous ideas. It was, as one admin noted, explicitly a “shaming” mechanism.¹⁵

In allowing such an article to stand, Wikipedia essentially took a side in a broader societal conflict. It aligned itself with the “Big Tech–Big Pharma–Big Government” consensus that views alternative health information as a threat to public order. This was no neutral stance; it was the embrace of a particular narrative in the contentious debate over health freedom and misinformation. And Wikipedia backed that narrative with the full weight of its authority, even as evidence (Meta’s data, etc.) undercut the narrative’s premise.

When an encyclopedia crosses from reporting facts to actively adjudicating disputes and punishing one side, it becomes something else: a tool of propaganda. That may sound harsh, but consider the admission that consensus now allows articles intended to shame living people.¹⁵ Consider how my page reads to a casual visitor: they would come away not just misinformed about me, but primed to dismiss anything associated with me (including the content on GreenMedInfo, which is itself heavily derided in the article). This serves the interests of certain industries and power structures by marginalizing one of their critics. In effect, Wikipedia lent its platform—wittingly or unwittingly—to an information war against health freedom advocates.

The ripple effects are profound. Many researchers, journalists, and laypeople still treat Wikipedia as a starting point for learning about a topic or person. If that starting point is poisoned—if it’s written in bad faith to discredit—it can skew perceptions across the board. In fields like medicine, where independent inquiry is vital but often stifled by commercial interests, this is especially dangerous. Wikipedia entries on topics like holistic therapies, supplement efficacy, vaccine safety, etc., often read as one-sided screeds that mirror the talking points of industry-funded skeptics. Legitimate debate is flattened; only the “approved” view is presented as truth. This monoculture of thought on Wikipedia isn’t just an internal community quirk—it actively shapes public knowledge and discourse, largely in ignorance of readers who assume they’re getting a consensus view of facts.

It’s telling that Facebook/Meta, a Big Tech entity not known for sympathy to “anti-vaxxers,” ultimately acknowledged that CCDH’s sweeping claims were bogus, yet Wikipedia did not correct course.²⁴ It suggests that Wikipedia’s internal dynamics (driven by certain editor factions or external influences) can be even more rigid and zealously attached to a narrative than corporate PR departments or government officials. When President Biden in July 2021 cited the “Disinformation Dozen” by saying “they’re killing people” with misinformation, that was a politicized exaggeration. But Wikipedia enshrined that spirit in an ostensibly factual entry, giving it far longer shelf life and credibility than a transient soundbite. At that moment, Wikipedia ceased to be a passive reference source and became an active participant in an agenda. It crossed over from cataloging knowledge to weaponizing knowledge.

[Video description: On July 19th, 2021, President Biden stated at a White House press conference: ““Facebook isn’t killing people. These 12 people are out there giving misinformation… It’s killing people…60% of the misinformation came from 12 individuals.”]

From my perspective—and that of the others who were on that notorious list—this felt like a betrayal. I’ve spent years building a database of research and engaging in scientific debates (albeit from a position critical of mainstream medicine). To see my name dragged through the mud on Wikipedia, with no realistic chance to fix it, was deeply disillusioning. As I’ve written in my personal essay, ”Wikipedia isn’t interested in truth. It’s interested in narrative control.”⁵⁷ That may not be universally true of all Wikipedia topics, but in my sphere it certainly rings accurate. Wikipedia’s credibility, in those areas, is shot.

The Beginning of the End—and the Search for Solutions

With Wikipedia’s flaws now laid bare for millions, some are asking: Is this the beginning of the end for Wikipedia as a trusted source? It very well could be. Trust, once lost, is hard to regain. And the trust in Wikipedia rested on an assumption of neutrality that has been systematically undermined. When readers realize that on certain topics they are effectively reading what one self-selected group wants them to believe, Wikipedia’s utility diminishes greatly. It may still be fine for uncontested topics—say, the height of Mount Everest or the basics of Impressionist art—but on any issue with political, medical, or social controversy, savvy readers will henceforth take Wikipedia with a hefty grain of salt.

What comes next? For one, there are calls for new approaches to online encyclopedias. Larry Sanger has been working on plans for a decentralized network of encyclopedic content, which he’s dubbed the “Encyclosphere.”⁵⁸ The idea is to remove centralized control—no single website or board of editors would have a monopoly on truth. Instead, multiple encyclopedias could coexist, networked together but with different editorial philosophies, and users could choose which they trust or view aggregate perspectives. “Imagine all the encyclopedias in the world, connected into one decentralized network, the way all the blogs are on the blogosphere,” Sanger explains.⁵⁸ No more one-size-fits-all Wikipedia. In theory, such a model could prevent the kind of capture that occurred on Wikipedia by ensuring competition and diversity of viewpoints. Of course, building a successful alternative is a daunting task—Wikipedia’s brand, resources, and network effects are enormous. But the current crisis of confidence might spur innovation and attract funders (Musk’s playful offer hints that big players are thinking about it).⁵⁴

Another avenue is legal accountability. As noted, Wikipedia itself enjoys strong immunity under Section 230—which, for now, shields platforms from liability for user-posted defamation. However, the broader “censorship industrial complex,” as some call it, is facing legal challenges. I have joined a federal lawsuit against the CCDH and others involved in disseminating the “Disinformation Dozen” narrative.³⁵ The suit alleges these groups colluded to violate the civil rights of those labeled as misinformation spreaders, among other claims. By dragging the likes of CCDH into court, plaintiffs aim to uncover any hidden coordination (for instance, with government entities or social media companies) and to seek redress for reputational harm. A successful outcome could not only vindicate me and others, but also send a warning to platforms like Wikipedia that one-sided defamation campaigns carry consequences, even if direct lawsuits against Wikipedia are stymied by immunity. Additionally, lawmakers are increasingly scrutinizing Section 230’s breadth; some have suggested that when a platform engages in editorializing (as opposed to neutral moderation), it should perhaps be treated more like a publisher. If Wikipedia is seen as crossing into editorial agendas, it could invite a regulatory rethink down the line.

For the time being, however, the most immediate solution is civic vigilance. Readers can no longer afford to take Wikipedia at face value, especially on any topic where bias might creep in. The old mantra “trust but verify” applies—verify not just the facts (via sources cited), but verify the sources themselves. Are they balanced? Are multiple perspectives represented? If an article’s citations are overwhelmingly from one camp (say, only pharmaceutical industry-linked sources on an entry about a holistic health practice), then the article likely has an ax to grind. Wikipedia’s openness can be its saving grace here: one can check the edit history, see which usernames are making controversial edits, even click discussion pages to read debates among editors. Those willing to dig will often find telltale signs of bias or conflict (as I did when I discovered the incriminating talk page quotes). In short, the onus is increasingly on readers to be their own fact-checkers when using Wikipedia.

Wikipedia’s current leadership and community would do well to heed the alarm bells and undertake reforms. Recommitting to the neutrality principle is essential if the site wants to salvage its reputation. That might mean purging the practice of using political hit pieces as sources, strictly enforcing BLP rules even when the subject is unpopular, and diversifying the editor base to avoid ideological echo chambers. It could also mean increasing transparency—for instance, flagging when an article has been the focus of organized editing campaigns, or when a source is being used despite known reliability concerns (e.g. a pop-up that says “Caution: this citation is from an advocacy group report, which is contested by XYZ”). Whether Wikipedia’s community has the will for such introspection is debatable; change has historically been slow and met resistance.

If nothing changes, we may indeed be witnessing the start of Wikipedia’s decline. People won’t stop seeking information online, but they will route around a broken system. Already, alternative wikis and specialized encyclopedias are popping up for topics like medicine (where doctors compile more clinically nuanced entries) and politics (where wikis with explicit ideological bent, left or right, say the quiet part out loud about their bias). In a way, that fragmentation is a reversion to the mean—perhaps it was unrealistic for one website to be the singular arbiter of truth on everything. The monopoly on knowledge that Wikipedia has held is looking less and less healthy for the internet’s information ecosystem.

My battle with Wikipedia, while deeply personal, is emblematic of a larger struggle over digital freedom and truth. The tactics used to marginalize me—coordinated defamation, platform policy manipulation, AI amplification—can and have been used against others who challenge powerful interests. But now those tactics are exposed. We have, in essence, caught Wikipedia with its guard down, the biased edits and embarrassing talk page admissions laid bare for analysis. Such clarity is rare. It offers an opportunity to push for change.

The ultimate call to action here is for transparency, accountability, and decentralization in our sources of knowledge. If Wikipedia is to continue to play a central role, it must confront the ways in which it has been hijacked and shore up its defenses against such capture. If it refuses or fails, then the mantle will fall to new solutions—be it Sanger’s Encyclosphere or some other innovation—to build a reference system that the public can trust. In the meantime, citizens, researchers, and readers must approach what they read online with a healthy skepticism and a demand for evidence over insinuation.

The stakes could not be higher. In the information age, controlling the narrative is akin to controlling reality for millions of people. Wikipedia has long been a dominant tool in that arena. The question now is whether it will continue to serve the open exchange of knowledge, or fully descend into being an arbiter of approved truth. My experience is a cautionary tale of the latter. But the backlash and awareness brewing in 2025 hint that the pendulum can still swing back. By shining a light on Wikipedia’s dark corners, I and others have done a public service. It’s up to all of us to insist that knowledge be set free—even if that means challenging our most trusted information sources, and building new ones when they fall short.

In the end, no encyclopedia—no matter how well-regarded—should be above scrutiny. Wikipedia once invited us to “edit boldly” in pursuit of accuracy. Now, we must criticize boldly in pursuit of the truth. And the truth, as my saga shows, will always find a way to surface. It’s our job to listen, learn, and never stop questioning the official story—on Wikipedia or anywhere else.

Call to Action

Through these trials, those of us who were targeted and defamed have found unity in a shared purpose: to seek justice—not only for ourselves, but for every American whose name has been unlawfully tarnished and whose speech has been suppressed.

Learn more about our federal civil rights lawsuit below:

🔥 🔥 On Trial for TRUTH: Replay of Live Conversation with the Trusted Twelve

They called them the “Disinformation Dozen” and tried to erase them from the internet.

References

Ji, Sayer. “They Came for My Name: Exposing Wikipedia’s Apex Predator Role in the Global Censorship Complex.” Substack, July 19, 2025.

Ibid.

Ibid.

“Why Wikipedia’s Attack on Sayer Ji is Wrong.” GreenMedInfo Blog, April 10, 2024.

Ji, “They Came for My Name.”

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

“’This Is Amazing!’: Tucker Carlson Stunned As Wikipedia Co-Founder Walks Him Through Site’s Blacklist.” The Daily Caller, September 29, 2025. https://dailycaller.com/2025/09/29/tucker-carlson-stunned-wikipedia-co-founder-walks-him-through-sites-blacklist/

“MAGA Melts Down Over Wikipedia ‘Blacklist.’” The Daily Beast, 2025. https://www.thedailybeast.com/maga-melts-down-over-wikipedia-blacklist/

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ji, “They Came for My Name.”

Ibid.

“Defamation Liability Implications of Sayer Ji’s Pre-Publication Notice to WSJ.” Legal Brief, September 2025.

Ji, “They Came for My Name.”

“Defamation Liability Implications.”

Ji, “They Came for My Name.”

Ibid.

“The Encyclopedia Hijacked: Wikipedia, the CIA, and the CCDH’s Campaign Against Sayer Ji and GreenMedInfo.” GreenMedInfo, June 21, 2024.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Sanger, Larry. “Introducing the Encyclosphere Project.” Knowledge Standards Foundation, October 2019. https://www.ksf.sanger.io/intro

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ji, “They Came for My Name.”

Ibid.

Ibid.

“Confronting Perplexity.AI’s Distorted Narrative on Sayer Ji.” 2024.

Ibid.

Ji, “They Came for My Name.”

Ibid.

Ibid.

“Why Wikipedia’s Attack on Sayer Ji is Wrong.”

Ji, Sayer. “WSJ Claims ‘Tylenol Deficiency’ Causes Autism—While Defaming My Work.” Substack, September 27, 2025.

Ibid.

“Defamation Liability Implications.”

Ji, “WSJ Claims ‘Tylenol Deficiency.’”

The Daily Caller, “Tucker Carlson Stunned.”

Ibid.

The Daily Beast, “MAGA Melts Down.”

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ji, “They Came for My Name.”

Sanger, “Introducing the Encyclosphere.”

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario